Thursday's Columns

May 15, 2025

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

Next Stop, Mars

Part 4

Ralph Pullmann’s column following this one this week is a trip down into the weeds of something called “the money system,” an occult world where a strange, made-up language is spoken by initiates, including Ralph, but not so much me. I've peeked through the curtain and learned a word or two, but I prefer floating high overhead, looking down on the weeds.

In his column below, I think Ralph is saying we don't know what to do because we don't know what's going on, or something to that effect.

I first met Ralph four or five years ago at a social gathering of thinker-types here in the Denver area. After some pleasantries around the beer keg, we quickly learned that we had a mutual interest in the subject of economics. He'd first started getting down into the weeds of it after loosing his businesses and most of his money in the Crash of 2008. I think for me it was just curiosity.

We gravitated to a corner of the room where conversing in an uncommon language was not considered impolite.

Since then, we’ve spent many hours on the phone, or out on the backyard patio going back and forth in economicese while Culley Jane’s inside reading a French novel.

It hadn’t taken Ralph and me long to realize that we agreed on the most important thing — that there’s enough for everybody and that everybody deserves to have enough. However, we were coming at it from two different angles.

I’m more the footloose philosopher type, wind in my hair, at the wheel of the big rig rollin' on down I-40 according to a plan I’m sure will get me to where I want to go.

Ralph’s more like the truck stop shop mechanics who rummage around down in the weeds of an engine when something mysterious goes wrong, like maybe on the way to San Bernardino when bright red warning lights start flashing randomly across the dash. Instinctively, I think about energy. Lyndon LaRouche (1922-2019), the philosophical economist, told me once in person in an old hotel room in Detroit in 1978, to focus on the "physical economy," which, he said, is a thermodynamic system.

So, of course! First thing, check the fuel gauge. There's plenty to make it all the way to Flagstaff, two hundred miles away. Pull over to the side of the road. Open the hood. A great mystery of tubes, wires and metal molded into shapes and forms. Limp on into the next truck stop with a mechanic on duty. He opens the hood. He pokes and prods and emerges with a diagnosis.

“It’s the money system,” he says.

“What’s that?” I ask.

“It’s complicated,” he says.

“I don’t have time for that. Just fix it. I'm expected. We'll never make it to the next step if I don't show up on time."

“Where ‘ya headed?”

“Mars.”

(to be continued...)

--30--

Capitalism's

Fundamental

Flaw

By

Ralph Pullmann

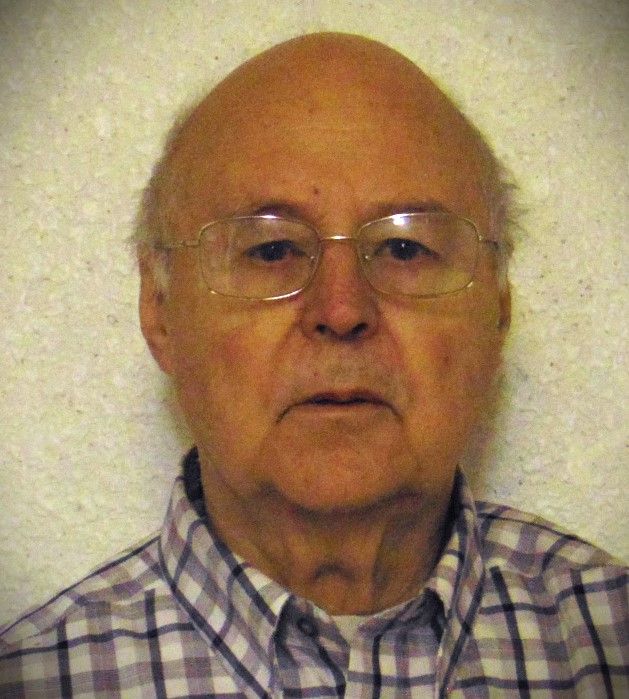

Ralph

While constructing economic models to illustrate the systemic threats facing our economy, I encountered what appears to be a fundamental flaw in capitalism.

To test this, I began by modeling the purist of capitalist frameworks, a simplified version of the economic philosophy of the so-called Austrian School, founded by Carl Menger in the late 19th century and which lies at the heart of modern Neoliberalism. This model of capitalism envisions minimal or no government intervention, leaving competitive markets alone to govern the relationships between producers of retail goods and consumers, theoretically arriving at a beneficial equilibrium, promising universal prosperity, “in the end.” The primary feature of modeling Austrian philosophy is to remove the government.

To explain where the flaw emerges, we first need to review a basic economic measure: Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In simplified form, GDP equals the sum of government spending, household consumption, net exports (exports minus imports), and investment. To keep things simple, I also removed foreign trade from the equation. This leaves household consumption and investment as the sole components of GDP.

Neoliberal economics typically assumes that investment represents funds borrowed from household savings. For the model, I allowed this assumption, but it quickly became evident that under the modeled conditions, household savings do not exist! Consequently, investment drops out, leaving household consumption as the only driver of GDP.

At this point, it becomes important to address a common misunderstanding: Why don't business-to-business transactions, when businesses buy from other businesses, count as part of GDP? The answer lies in how GDP measures final output. The prices paid by retail corporations to their suppliers already encapsulate the costs and profits of those upstream firms. If we counted those intermediate transactions separately, we would be double counting the same production. Thus, all upstream corporate activity is ultimately embedded in the costs faced by retail corporations.

In the model, retail corporations face two primary costs: wages paid to households, providing the only income households receive, and payments to upstream (non-retail) corporations for goods and services. Retail corporations add a profit margin to these costs to set their final selling price to households.

When the model tracks the flow of money, a critical problem becomes apparent: households only receive wages, yet are expected to buy the full output of the economy. According to real-world data, wages typically account for just 20–35% of corporate income, though this varies by industry. In the model, this dynamic plays out as a consistent shortfall: households, with income limited to wages, can afford to purchase only a fraction of the goods and services produced.

One might expect that upstream corporations, those selling inputs to the retailers, could close this gap by paying their own wages. However, in the model, the wages paid by upstream firms are already reflected in the prices charged to retail corporations. Like the retailers, upstream corporations also apply their own profit margins. The model shows that this recursive layering of costs and profits leaves the aggregate wages paid across the entire production chain insufficient to match the total value sold by retailers.

The model also demonstrates that if both retail and upstream corporations reduc their profits to zero, the system reaches equilibrium: households earn enough to purchase all production. But as soon as any profit margin is reintroduced, a gap re-emerges between household purchasing power and total output. This gap results in unsold inventory, which forces layoffs, reducing wages further and accelerating economic contraction.

Real-world economies are more complex. We mitigate this problem through household borrowing, inflation, and government deficit spending, injecting additional purchasing power through welfare, subsidies, and transfer payments.

The model implies that without these injections, a capitalist economy constrained by profit margins cannot sustain itself. Over time, this creates a systemic dependency on both household and government debt. The flaw revealed by this modeling exercise is not a policy error, but a design feature of capitalism itself: when profits are present, household wages’ purchasing power becomes structurally insufficient to sustain full consumption of output.

Fortunately, there are alternatives without abandoning capitalism’s productive strengths.