Thursday's Columns

July 10, 2025

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

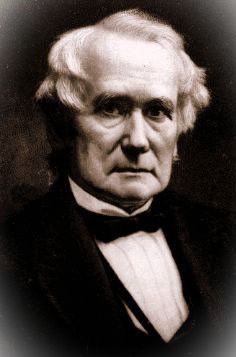

Henry Charles Carey (1793-1879)

“Two systems are before the world… One looks to pauperism, ignorance, depopulation and barbarism: the other to increasing wealth, comfort, intelligence, combination of action, and civilization. One looks toward universal war; the other to universal peace. One is the English System: the other we may be proud to call the American System, for it is the only one ever devised the tendency of which was that of elevating while equalizing the condition of man throughout the world. Such is the true mission of the people of these United States.”

Henry Charles Carey

The Harmony of Interests (1851)

The American System

I had been hearing that Fourth of July celebrations were being cancelled all over the country, for whatever reason. It had always seemed to me that The Fourth was a day to think about America in the most positive light, even during Vietnam. Maybe the view is getting cloudy.

Growing up in Iron Mountain, my small home town at the edge of the northern woods, the Fourth was all about everybody getting together for the parade down Main Street in the morning and then out to Lake Antoine for games and family picnics, gatherings in the park of all the town’s families, the Italians and Swedes, Finlanders and French-Canadians, Catholics and Lutherans alike. Grandparents swapping tall tales and Old World recipes. Then, at night, the town came together again to watch the fireworks on Millie Hill.

No wonder, then, that, to me, the Fourth of July has always been associated in my mind with the idea of association.

A big news story in Denver this past week was the city’s announcement that it can no longer afford to help immigrants hiding from ICE in run-down shelters without cutting services to real Americans. But on a positive note, the city will buy them bus tickets to go someplace else.

I woke up late on the morning of the Fourth to a nagging back because I’d worked on the wood pile the day before. Culley Jane had coffee ready and asked me if I knew what I was going to write about for this week’s column.

“Association,” I said.

When I think about the idealized America I wish to remember and celebrate on the Fourth of July, I think about association. It’s not as colorful as Yankee Doodle, but it’s more real.

The principle of association was at the heart of what, in the 19th century, was widely known as the American System. Its roots went back to Hamilton and can be seen emerging in the federally funded construction of roads and bridges and tunnels over and through the Appalachians to the land between the mountains. In 1826, the Erie Canal was completed, bringing the timbermen and miners of the Great Lakes region into closer association with manufacturers along the Atlantic Coast.

There were, of course, objectors to the undertakings. There were lively debates in Congress. A sectional coalition of southern planters closely tied to England and the cotton trade objected to their federal dollars being used for projects that looked like pork for the benefit of northerners alone.

Supporters, on the other hand, led by Henry Clay of Kentucky, argued that the prairie grains and the iron and copper of the Mesabi Range could benefit the whole of the new nation. The projects, they argued, were American systems.

Clay was defeated by Jackson in the Presidential election of 1830. Sectionalism grew. An ugly boil developed between we and thee, threatening to burst open. An entire civilization of thems was deported to Oklahoma Territory in a Trail of Tears. The ideas of the American System were fading.

That’s when Henry Carey burst upon the scene. He was the son of Mathew Carey, an Irish revolutionary who emigrated to America and operated secretly within Franklin’s circles during Revolutionary times.

Like his father, Henry Carey was a printer, pamphleteer, journalist and a student of what was then called “political economy.” In 1835, when he was 42 years old, he resurrected the fading ideas of the American System and spread them throughout the world. Marx said he was the only American economist worth reading. He became Lincoln’s most important economic advisor. Greenbacks were very much Carey’s idea. While financing a million-man army to fight a continental war, the new national currency built a railroad to the Pacific.

During the 1860s, while the sale of Alaska was being negotiated, one of Carey’s American System allies, William Gilpin, the first territorial governor of Colorado, started pushing the idea of a transcontinental project to build a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting Alaska and Russia, increasing the association between the peoples of two great land masses, exponentially increasing the wealth of all, decreasing the likelihood of war.

After Carey's death in 1876, his students and co-conspiracists were instrumental in the creation of the American Economic Association, which gravitated to the economics department of Columbia University, which produced the core of FDR’s “Brains Trust” – Rex Tugwell, Raymond Moley, Adolph Berle.

The American System reemerged as the New Deal; a sub-continent was transformed; great, sprawling projects on the Columbia and Colorado rivers for power and irrigation; TVA; the St. Lawrence Seaway; rural electrification. Then the Eisenhower generation built the Interstate System. Then Kennedy pointed us towards the moon, and we went to the moon.

Then it was time for the next generation to take over, my generation, and we sat back and watched the great projects grow old and never went back to the moon.

Henry Carey wrote that all his thinking was based on one great principle, the Principle of Association. Unlike the British System, which argued that wealth was produced by buying cheap and selling dear, the American System was based on the conviction that all wealth is produced by people in association with one another; raising crops and children; melting ore. Simply put, the total wealth produced by a group of isolated homesteads on an isolated frontier increases exponentially when everybody is linked together by roads and phones and pot-luck dinners.

The night of the Fourth of July last week I sat out on our backyard patio with a beer taking in the sounds and sights of neighborhood kids with firecrackers and bottle rockets filling the air with colorful sparkles.

America in its most positive light.

In my mind, at least, The American System still exists.

--30--

Letter to

The Staff of Westphalia

from

Andreas Hug

Guelph, Ontario

To the Staff of Westphalia:

I found last week's "Our Story" column about Culley Jane's birthday party interesting, especially the reference to Leibniz. Not being too familiar with his philosophy and works, I went to a Swiss website to learn more about him. I'm forwarding to you what I found there, including the picture of the portrait of Leibniz and the German caption that went with it, which I've translated for your readers. Picture credit for the painting: Christoph Bernhard Francke, about 1700; Duke Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, PD.

Sincerely:

Andreas Hug

Geburt von Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Der deutsche Universalgelehrte, Philosoph, Diplomat, Mathematiker und Historiker gilt als einer der wichtigsten Denker des ausgehenden 17. und beginnenden 18. Jahrhunderts sowie einer der wichtigsten Vordenker der Aufklärung. Von ihm stammt der Ausspruch: Beim Erwachen hatte ich schon so viele Einfälle, dass der Tag nicht ausreichte, um sie niederzuschreiben.» Bild: Porträt von Christoph Bernhard Francke, um 1700; Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig, PD

The German universal scholar, philosopher, diplomat, mathematician and historian is considered to be one of the most important thinkers of the end of the 17th and of the beginning of the 18th centuries and also one of the most important prophets of the Enlightenment. He is the one who coined the saying: “When I woke up I already had so many ideas, that the day was not long enough to write them all down.”