Thursday's Columns

August 7, 2025

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

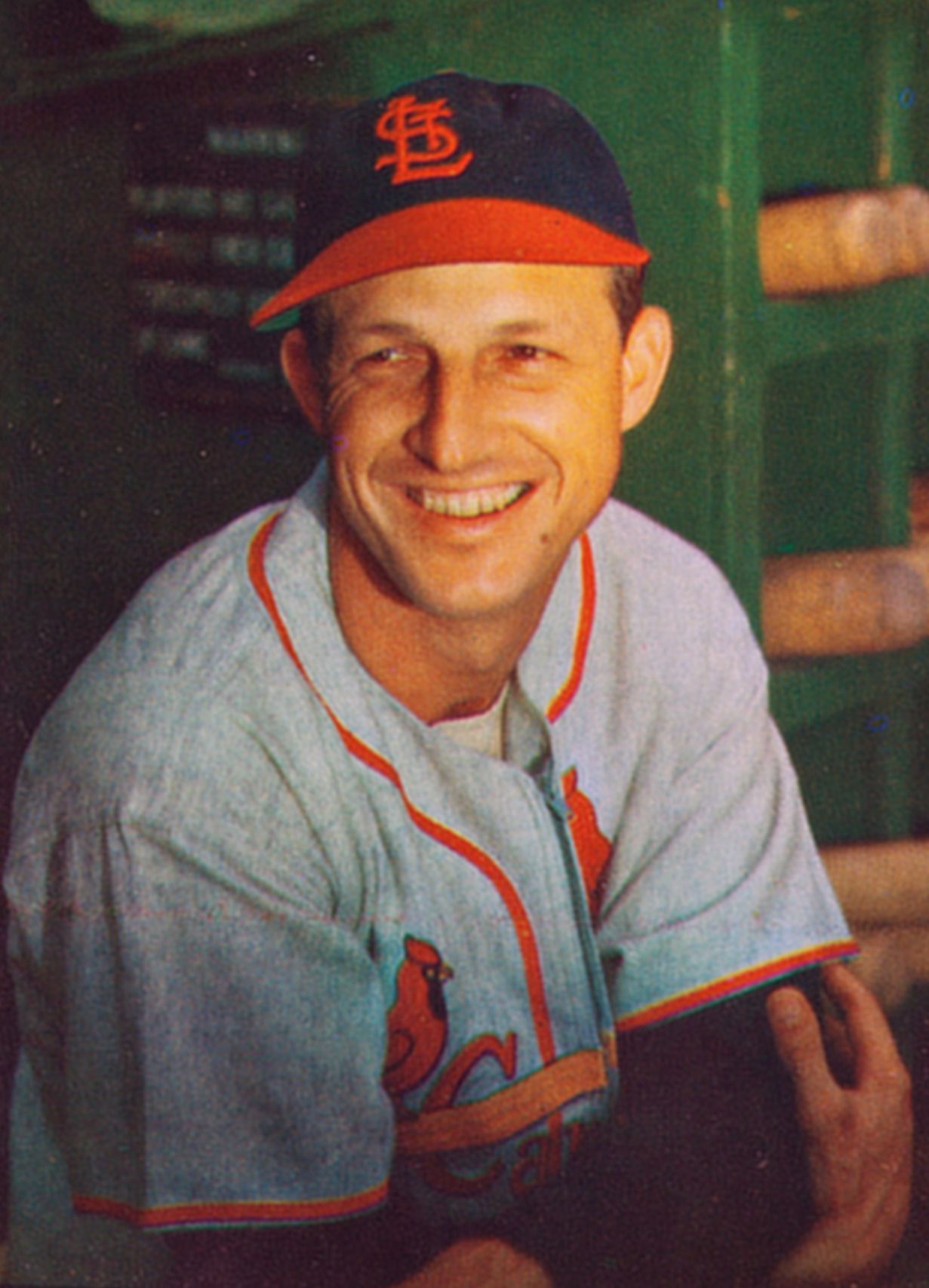

Stan "The Man" Musial

If I write anything over the next few weeks it will be a miracle. I’m swamped. Everything’s going on all around me here all at once. I can’t do it all by myself.

Construction workers will be here soon to replace all the windows in the house, disrupting everything not already disrupted. Upcoming doctor appointments to talk about things I don’t want to talk about. Finances. Passwords. The lawn.

And pretty soon Culley Jane is flying off to San Francisco to visit her brother and sister-in-law and I’ll be home alone with the cats, who’ll let me know I’m not doing anything right — following my every move with their cat eyes, like what’s the matter with you? The food dish is six inches out of place. The litter scooper is on the wrong side of the box.

While in San Francisco, Culley Jane will be meeting up with Jean Schiffman. Westphalia is publishing Jean’s most recent book: “Alzheimer’s: A Daughter Says Goodbye.” It’s been a two-year project and is in the final hectic editing phase before going into production.

After Culley Jane gets back, her nephew from Portland will be visiting for a few days. He and his wife are thinking about moving to France.

In the meantime, I never know when I’m going to get a call-back from contacts and sources who help me know what’s going on, like from Stephen Dean, former head of the U.S. magnetic confinement fusion program, or from the CEO of USA RareEarths, Inc.

Even when things are settled down, there never seems to be enough time to know everything I want to know and winter is peeking around the corner and there’s still a big pile of wood out back to be cut up, split and stacked in case AI sucks up all the electricity and things go dark just when a big blizzard is coming at us down off the Rockies.

Then, right after the nephew leaves, Culley Jane and I will be driving to Walla Walla, Washington, to visit Pat Henry and Mary Anne O’Neil (married with their own last names, just like Culley Jane and me).

Culley Jane has known Pat and Mary Anne since her graduate school days in the 70s at the University of Oregon. They’re retired professors too.

I could tell all kinds of stories about those two. Pat and I have become great friends. Maybe besties. He grew up in New York City, son of an Irish cop. How he got to be an internationally recognized scholar of Renaissance and Enlightenment-era French literature — Montaigne and Voltaire and such — is beyond me.

He’s also an authority on the Jewish Holocaust and wrote a book about a rural area in France — the Vivarais Plateau in the Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes region of South-Central France — where the locals risked their lives to protect Jews from the Nazis during WWII. He was recently in Israel to accept an award on their behalf.

Now he’s started work on a new book. It’s about Daniel Berrigan, the Catholic priest and peace activist during the Vietnam years. I guess Pat knew him personally and knew him well, almost like besties. They were friends from 1976 until Berrigan died in 2016.

I first met Pat maybe four years ago at their place. Right off the bat we hit it off. Lounged out in comfortable living room chairs drinking local wines and beer while Culley Jane and Mary Anne were off in the kitchen talking about other things, we learned that we had both been big fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers before the team moved to L.A. in ’58.

He was amazed when I started rattling off the lineup: Campanella behind home plate, Newcombe and “Preacher” Roe on the mound, Jacki Robinson, “Pee Wee” Reese, “Junior” Gilliam, the “Duke,” Hodges, Furillo, Erskine, Labine…

“I’ll be damned,” he said, slapping his knee, like running into somebody out of the blue waiting for a bus on a street corner who knew about, or had ever even heard of Montaigne.

To me, the 50s Dodgers were faces on Topp’s baseball cards. To Pat, they were his boyhood heroes, models of what he should aspire to be. Growing up, he went to games “all the time.” Ebbets Field was a short subway ride from where his family lived in Queens. Sometimes his dad would drive him to the games.

He took me downstairs to show me his wine collection and office. On a ledge above the desk where he wrote about war and peace was an autographed picture of Stan “The Man” Musial, beautifully framed.

“Musial!” I howled, loud enough that the women upstairs could hear me. “He was my biggest childhood hero. I got to see him play once, late in his career. Dad drove us down for a game in Milwaukee. Dad said I might have made it to the Big Leagues had I not been determined in Little League to stand like Musial at the plate… crouched at the knees, bat straight up held high. But I figured the idea was to be like him. He never got into trouble. He gave up years during his prime to serve his country. He seemed plain and just nice, like a kid off the farm, but did a good job and became famous without thumping his chest. He was humble. He let his bat do the talking. Unlike the big home run hitters of his day, with their muscled up towering drives into the stands, Musial hit triples, liners on a tightrope down into the corners, sliding into third, counting on his teammates to get him home.”

I told Pat about the time I met Musial in person. It was 1974. He was retired by then and I was a young reporter at a newspaper in the St. Louis area. Sometimes the sports editor let me use his pass to the Busch Stadium press box, where the beer and food was free. Sometimes old-timers would stop by to mingle with the announcers, old friends and teammates. One time, when I was there, it was Musial. He was looking over the lavish tables of catered food, like just another face in the crowd. I was nervous, but I had to go up to him and tell him that when I was a kid he was my hero and that I stood at the plate like him and that I was trying to do a good job.

He looked up from the plastic plate he was filling with veggies and cheese. He smiled at me like I’d helped make his day a better day. He nodded, shook my hand and said I should try the avocado dip.

As Pat was uncorking one of his “special” bottles of French red wines that he reserved, he said, for “special occasions,” he said in New Yoker Irish brogue: “Betch’ya don’t know where Musial got the name, ‘The Man.’”

I didn’t. “He was born with it?”

“He got it from the Brooklyn Dodger fans.”

“No… Really?”

“I was there. I know. He drove us nuts. We couldn’t get him out. Pitch ‘em anywhere — high, low, under the chin — didn’t matter… like he could see the ball, the rotation of the seams, coming at him in slow motion.”

Pat refilled my glass.

“Especially,” he raced on, “during tight pennant races, we hated to see the Cardinals coming to town. He was our nemesis. But the Brooklyn fans didn’t boo him. They started chanting a name, ‘The Man,’ and it stuck.”

“I can see it, the scene, clearly in my mind,” I said, touching glasses with Pat. “I hear the crowd chanting… ‘The Man. The Man.’ Berrigan brushes the dirt from his uniform after sliding into third. Ninety feet to go. He can’t do it alone. Counting on his teammates to get him home.”

--30--

Another Story

by

Darwyn Van Wye

by

Craig Chambers

Denver Confluence Writers

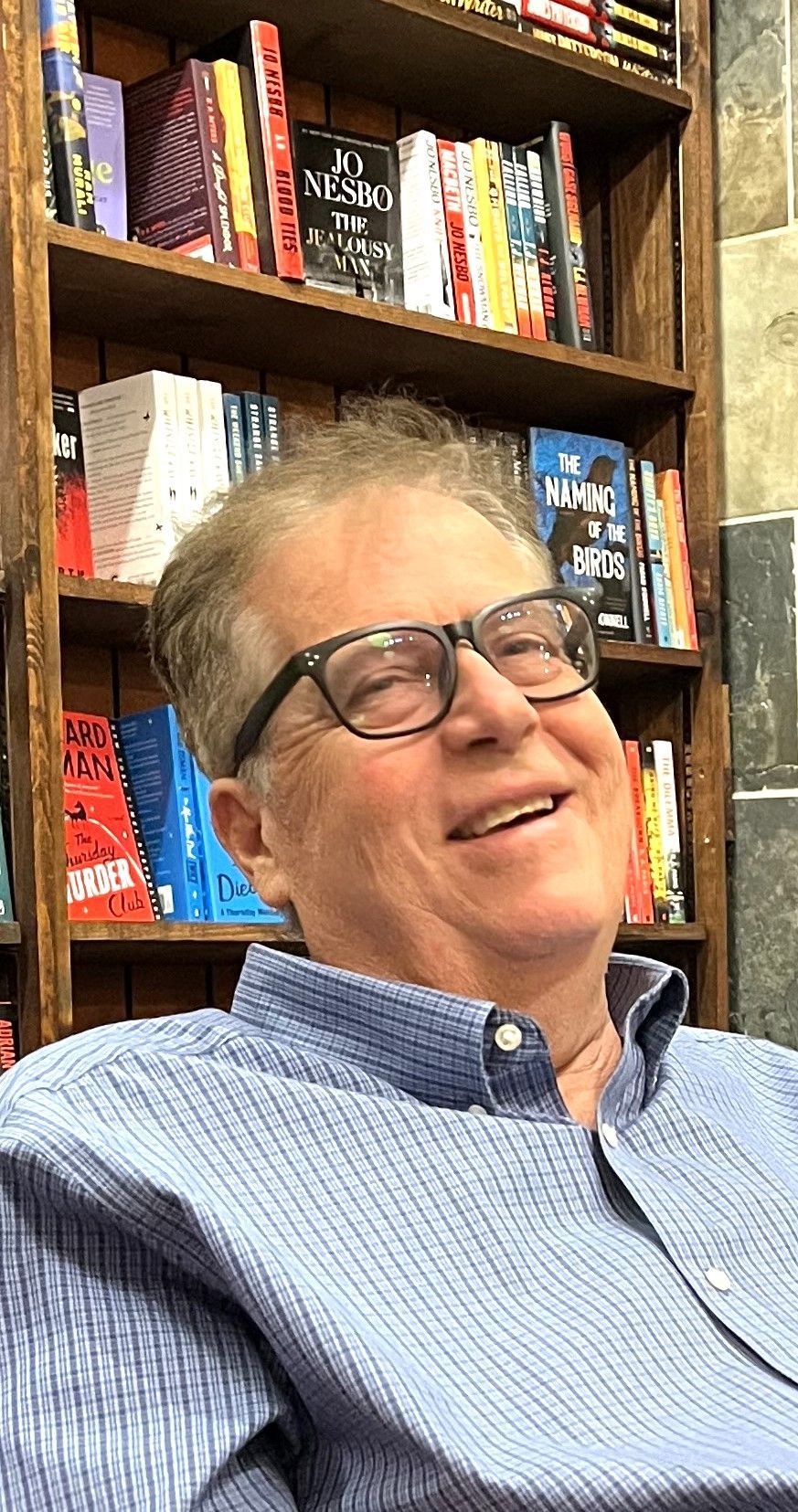

Craig Chambers

Let Me Tell You

Something

About Myself

by

Darwyn Van Wye

Quinn County Attorney

Real Estate Broker

Legendary Writer on the Side

I like to pretend we’re in a support group for people with personality disorders. We’re sitting around in a circle on folded chairs in a room with asbestos ceiling and asbestos tile floors.

“Hello, I’m Darwyn Van Wye,” I say. “But you can call me anything you want.”

Let me tell you something about myself. I speak an ancient, cryptic language. It’s called English.

I’m a lawyer, so it’s important I’m not too reflective. I’m afraid if I look too carefully at myself, I won’t like what I see.

For example, I went to a restaurant and the waitress tried to help me. She smiled and handed me a menu. She was young. Her name was Violet. She looked like a violet too, her hair dyed purple. I guess she’s what you’d call a millennial.

“What would you like to drink?” She asked.

“Tang,” I said. And I didn’t say anything else.

She looked confused. I could see she was thinking. Violet was trying to be a good waitress, but she didn’t know what Tang was.

I don’t even drink Tang. Too much sugar.