Thursday's Columns

June 26, 2025

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

My Enemy

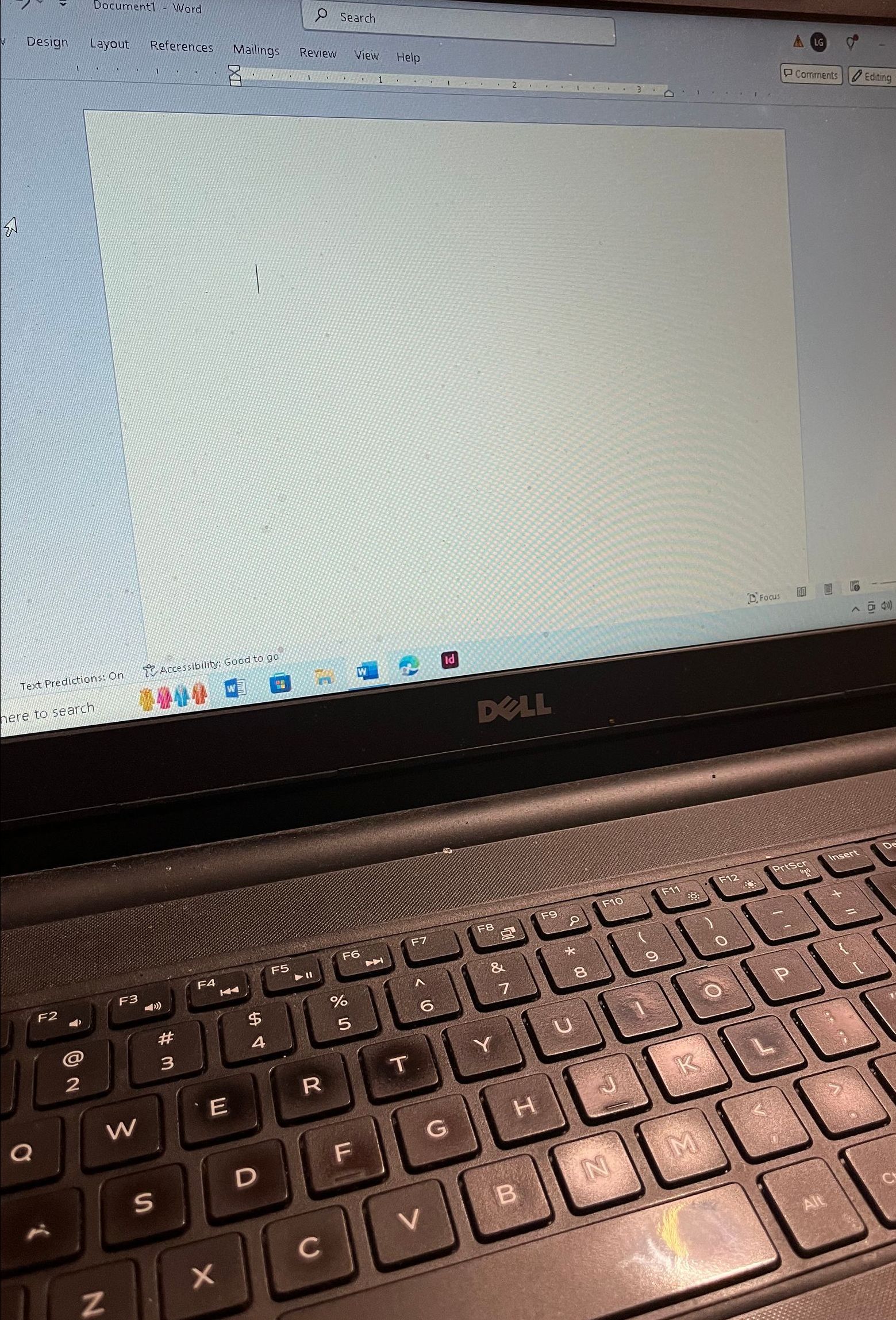

The blank computer screen is my enemy, a mirror reflecting my mind every time I sit down to start writing my next Our Story column. Blank screen, blank mind — twin vacuums that only exist to be filled and brought back to life with the brushstrokes of morphogenic ideas… What’s going on? What’s the news? War? Seems like there’s always a war. I look out the window and the sky is blue. The horizon is a range of snow-capped mountains. Culley Jane and I have enough of what we need. A cat sleeps with one eye open. The sound of neighborhood kids playing in the street. So, there are also closets of peace in my morphogenic world waiting to be expressed like breath in the language of my perpetually soon-to-be finished novel about the biggest story in the world.

I really need to get back to work on my novel.

My novel has a simple plot:

A scientist named Rebecca, who plays the violin and teaches the mathematical metaphysics at a small university way up north in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan on the southern shore of Lake Superior, discovers the solution to all our problems. Well, not exactly problems like marital squabbles and neighbors who play their music too loud, but the kinds of problems that nations of people go to war over.

After submitting a paper announcing her discovery to an international academic journal, the CIA swoops in to classify her work as Top Secret, making it illegal for the world to know that there’s really no problem so big that it couldn’t be solved with a handshake over a couple beers.

Frustrated by ongoing unnecessary wars, Rebecca decides to become a whistleblower and calls a former student of hers who’d become a newspaper reporter in Detroit — an investigative reporter.

The reporter, an investigative reporter named Benny — Benjamin T. Profante — becomes the main character in the novel.

The 70s had been a good time to be an investigative reporter, especially after Woodward and Bernstein, played by Dustin Hoffman and what’s-his-name, made it look glamorous. In the social ordering of a big city newsroom, investigative reporters were at the top. When he met a girl in a bar who seemed interested, Benny always told her that he was an “investigative” reporter.

Starting out at small town dailies after taking off to become a famous writer like Kerouac or Hemingway, Benny started winning awards for his investigative reporting and was moving up because he knew where to look for stories that other reporters, sitting in a meeting or at a press conference, didn’t know were there.

Some said he had an “instinct,” or a “nose for news.” But he figured it was just common sense. Already by high school he knew you could learn as much at the pool hall as you could at church, depending on what you were looking for.

He came up with the leads to his investigative stories in worker bars with old timers and pool tables. Like the one about the county probate judge who kept vodka in the water decanter on his trial bench. Benny found out about that by drinking beer after work with the courthouse janitor.

He got to know the waitresses and groundskeepers at the local country club. Quoting “informed sources,” he revealed that the mayor only tipped the waitress with “big breasts” and that one of the county commissioners consistently cheated on his scorecard.

Once he got to Detroit, Benny was assigned to the Hoffa case. It was the biggest story in Detroit at the time, bigger even than the oil embargoes and long lines at the gas pump.

The general consensus in the newsroom was that Hoffa'd been whacked for crossing a mob boss in a backroom deal. Great front page stuff, a gripping who-done-it with a long list of shady underworld suspects with Italian names and cliff-hangers to get readers to the next edition. Ad sales were up.

But Benny challenged the narrative.

Instead of chasing down Justice Department and criminal underworld leads, he started hanging around the city’s warehouse districts, in the bars and diners where dock workers and truckers hung out and everybody was a Teamster and Hoffa was everybody’s hero.

Benny got himself invited into their homes. Sitting around kitchen tables between mom with the baby and gramps drinking schnapps with his beer, Benny took notes while the family told their Hoffa story to the world. Their Hoffa had the power to shut down the vital national motion of the things people need. But the Teamster boss didn’t use his power to build himself a castle on the hill. He never left the neighborhood in Pontiac where he’d grown up. He used his power to get the families of dock workers and truckers a better deal. Before Hoffa and the national freight contracts in the early 60s, the lives of the families of dockworkers and truckers had been a hardscrabble affair. Now they had middle class homes and a wooded vacation lot on a lake up north.

Benny wrote their stories and suffered the consequences of challenging a general consensus. His stories raised unwelcome questions going to the heart of motive. Had Hoffa been killed because he’d screwed with the mob, or because he was a hero sacrificing it all to help raise people up to a higher level? Maybe the mob was just doing a job, but who had ordered the hit? And why? The question expanded the list of potential suspects into social circles beyond the Hollywood version of organized crime.

That’s when things in the novel start happening fast:

A general consensus forms in the newsroom — this new guy, this Benny, is a loose cannon, maybe a conspiracy theorist.

Management takes him off the Hoffa case and assigns him to the early morning police beat and to writing obituaries when he’s got any free time.

At this point in the novel, Benny’s feeling mighty low, but just then his phone rings and it’s a professor he had known in college and the biggest story in the world falls into his lap.