Thursday's Columns

September 5, 2024

(episode two)

The Travails of

Darwyn Van Wye,

Lawyer, Real Estate Broker

by

Craig Chambers

After being fed a summary of Craig Chamber's latest Darwyn Van Wye episode, the Artificial Intelligence Division of Westphalia Publishing's Language Department produced the above image of the Overtime Bar. Not exactly a sports bar, but we think it captures a deeper meaning to the story that maybe even the writer was not aware of. You'd expect something like that from an Artificial Intelligence.

Every Single Day

(I Feel Like Crying)

Annie and Abby, my twin granddaughters, they’re nine. They’re identical so they have their own language. Only I understand them. Especially Annie. She’s the cuddly, crabby one. She cries all the time.

Today it’s their birthday party, each twin was allowed to invite one friend. They’re not too good at math so there are about a dozen nine-year-olds playing in the yard.

Annie doesn’t like the pizza. There’s No Pepperoni. When she sees the Pepperoni Pizza, she cries again. She’s no longer hungry. The pizza’s too cold, Abby took the bigger slice.

Annie Adele Van Wye!

She’s just like me: Darwyn “Wyn” Van Wye. I’m a real estate broker, a family law and custody attorney. I run my practice out of a sports bar called The Overtime. I see people on their worst day. The day the husband cheated. The day the wife left. The day the husband kidnapped the kids or put a knife to the wife’s throat. Every single day, I feel like crying, too.

=The End=

=The Beginning=

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

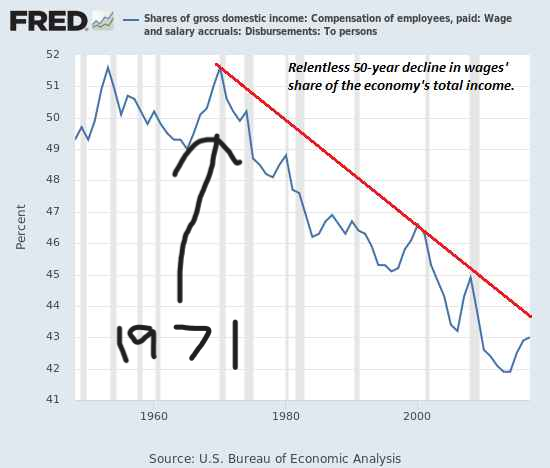

Wages’ share of Gross Domestic Income, 1948 to 2022. Wages defined as “Compensation of employees, paid: Wage and salary accruals: Disbursements: To persons.” Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; published in FRED, Federal Reserve Economic Data, 2022.

A Book About Economics

The town of Aurora, Colorado, the home of Westphalia Publishing’s world headquarters, woke one morning last week to find itself the focus of a big story making its way across the internet and national news wires. Reportedly, a Venezuelan gang was taking over apartment complexes at gunpoint here. There were videos. Young guys had scary looking rifles that looked like machine guns, just a couple miles down Buckley Avenue from where we live on a quiet suburban street.

Everybody in town was talking about it. I called friends, “Did you hear the news?” “Of course,” they said. I could just imagine the topic of conversations at the yoga class for seniors at the county recreation center -- nothing about aches and stretches, but more like in the nature of “Dear Lord! What on earth is Happening?”

I think I have a pretty good idea. I’m an ace reporter. It’s my job.

Hemingway said he spent his whole life trying to write “one true sentence.” James Carville uttered one true political sentence during Clinton’s first Presidential campaign. He said, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Plato said the quest for truth (which is a reporter’s job) begins with a hypothesis of the higher hypothesis.

My hypothesis of the higher hypothesis came to me like in a flash on September 11, 2001. Things, it felt like to me, things in general, seemed to be going downhill.

I was an over-the-road trucker at the time. I was just leaving the Atlantic docks in Virginia Beach with a load of European beer going to Chicago when I heard the first reports over my Sirius XM satellite radio. Planes flying into buildings. I got over the Appalachians as fast as I could.

The cab, an over-the-road trucker’s home, can be a lonely place at night with just the vibrations of the pavement and the mechanically orchestrated symphony of one big ass Detroit diesel engine pulling you along a striped, black path swarming with moving lights.

From within the cab of a semi crossing a continent, it’s easy to feel separated from all that’s “out there.” But the night of 9/11, somewhere on I-80 in Ohio, I felt like I’d been swept up into something larger than my own little world, like I was in a raft without oars on a powerful river -- flowing downhill, whether into a placid lake, or over Niagara Falls, I did not know. I only knew that it felt like things in general were going downhill.

I could see it empirically because I had something to compare it to. I grew up in the 50s when it felt like things in general were going uphill. The Idea of Progress was scientific fact. Mister Wizard said so. We were going to the moon. We finished our higher educations with our dreams intact, but now our kids start out with debt.

Sitting around the lunch counters at truck stop cafes I started asking other drivers if it felt to them, too, like that things in general were going downhill. Lots of them had been around since before Hoffa got whacked. Ya, they said, rubbing their chins, downhill.

I started thinking like a reporter. What had happened? I decided to investigate, even if it took me the rest of my life to write a book about economics.

I decided to start with the What, as in the Who, What, When, Where and Why of every story?

From my old reporter days, I knew that to get the What, it usually helps to first get the When. Only then could you even begin to tackle the Who’s and Why's.

So, had there been a documentable point in time when things that had been going uphill started to go downhill, and kept going downhill into the 21st century? Obviously, I would have to measure the economy. I reasoned that an economy is people making things and consuming things. Obviously, I couldn’t measure all the things that people make and consume, but I could measure the things that things are made out of – the elements of the Periodic Table.

It took a couple of years, but around 2005, after getting internet access in the cab of my truck, I felt like I had a plausible answer. The U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, had the entire 20th century all laid out in spreadsheets – total U.S. production and consumption of Periodic elements from arsenic to zinc, the iron for steel, aluminum for kitchen pans, sulphur for compounds, gold for dentist fillings and on and on.

Parked for the night in truck stops and along Interstate exit ramps all over the country, I taught myself how to make crude graphs of the Bureau of Mines spreadsheets and then other socio-economic data.

Here’s a couple of examples of what I was seeing. The work of a computer amateur, for sure, but a picture began to emerge...

STEEL PRODUCTION (1900-2001)

Total annual U.S. domestic steel production. Source: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines.

PRISON POPULATION RATE (1925 - 2002)

Source: NEBER, National Bureau of Economic Research

I made dozens of graphs, piecing them together in my mind like frames of a movie. The plot was so obvious that it was laughable. It was the story of America in the 20th century, the American Century; the story of men and women who had grown up in good homes; matured into strong, productive adults; and, then, at a particular point in time, began to fade in the direction of a mathematically predictable entropic end.

I didn’t like what I was seeing, but at least I finally had my When and could refine the question. Instead of “What happened?” it became “What happened in 1971?”

That’s when I recalled where I was on the night of August 15, 1971, a 23-year-old rookie reporter in a neighborhood bar in Hillsdale, Michigan, getting ready to watch Bonanza when Nixon suddenly appears to announce (buried in the middle of his speech) a “new international monetary system.”

One night around 2005 I was parked out in the middle of the Mohave Desert lying on the roof of my truck looking up into our milky universe when the obvious next question came to me – “If it was a new system, what was the old system?” I had no idea. But it seemed to me like an important thing to know because something had happened in 1971, some kind of big deal -- big enough to change the course of a mighty river of history. Definitely Front-Page News, above the fold.