Thursday's Columns

August 31, 2023

Our Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

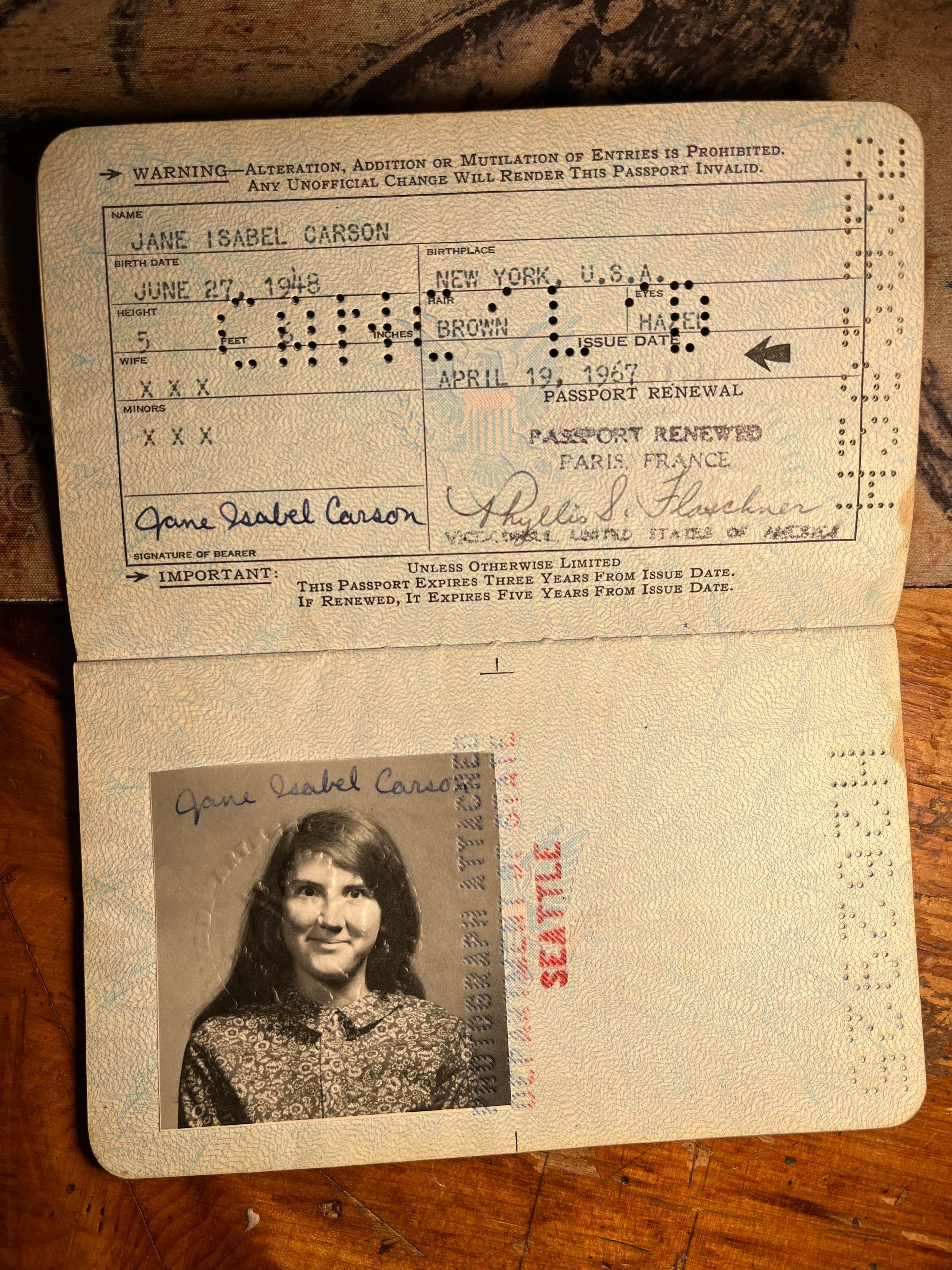

Culley Jane's first passport in 1968

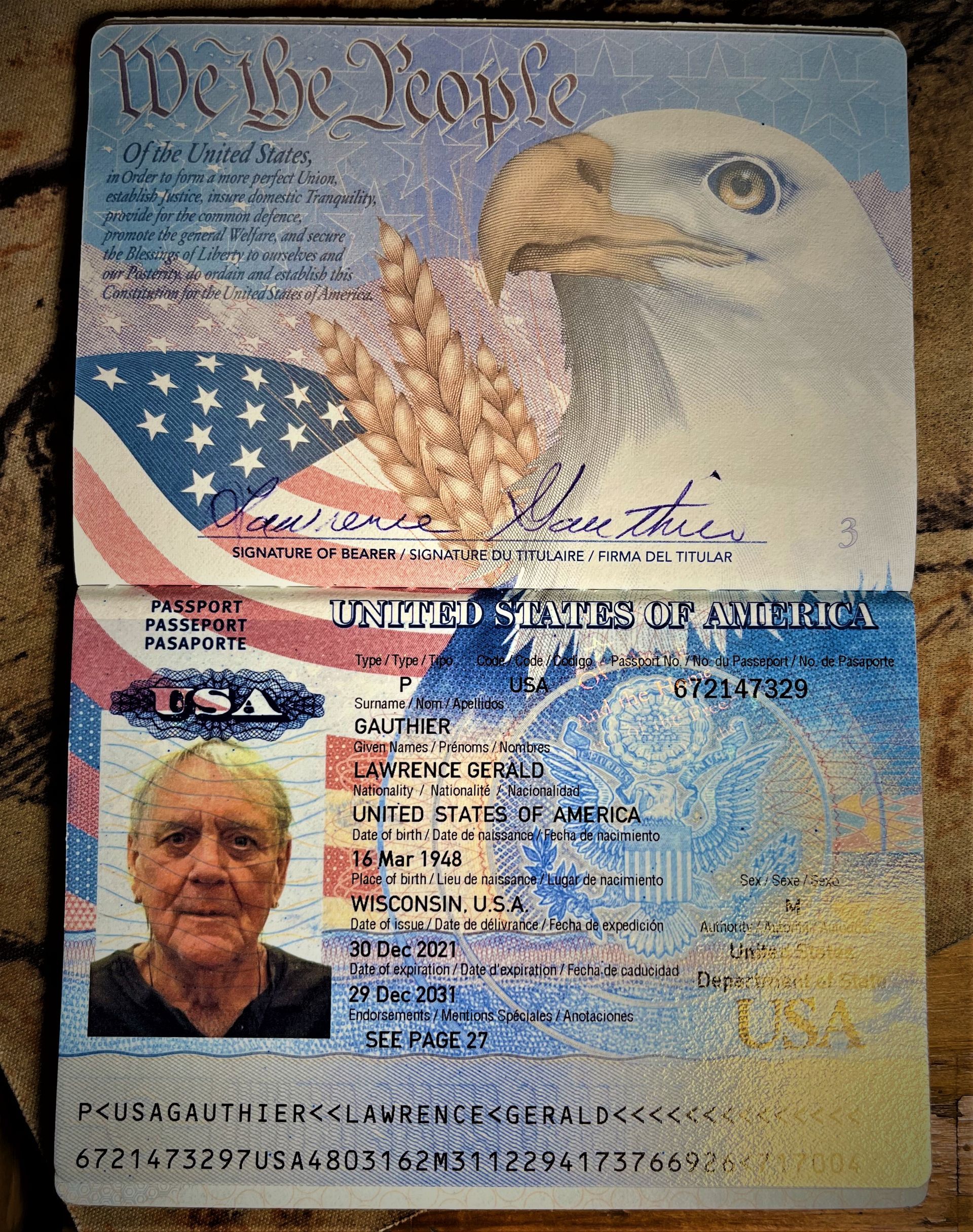

My first passport in 2023

AMERICANS IN EUROPE

(Part 12)

My wife, Culley Jane the retired professor, was 19 years old the first time she went to Europe. She wanted to study languages.

Me, I was 75 years old the first time I went to Europe. I wanted to get a picture of me at the ITER construction site and I wanted our 15-year-old granddaughter, River, to see for herself what humanity is capable of. It would be great if I got to wear a hardhat.

The big fusion reactor -- the International Test Experimental Reactor, or ITER -- is located in the far southeast corner of France, not too far from the Mediterranean and France’s border with Italy, which made the region an easy grab for the early Roman Empire. Tourist brochures said there were still lots of Roman ruins in the area, officially known as the département Bouches-du-Rhóne, or “mouths of the Rhône,” not to be confused with the Rhine.

To get there from where we started out in Germany, we followed ancient trails formed by the lay of the land, except in the mountainous lands of Switzerland where people had to build concrete tunnels and steel bridges to get around.

From Heidelberg, we followed the Rhine to Switzerland, where it veered off in a direction we weren’t going.

Most all of Europe’s major river systems begin in the highest peaks of the Swiss Alps. Over the centuries, national borders have come and gone and changed hands by force or marriage, but the veins and capillaries of the water system of the whole have drawn their life from Switzerland. I’ve heard it called “the water tower” of Europe… the source… where money is hidden from view. It’s where arguably the most powerful family in the history of the world -- the Habsburgs -- started out as the toughest guys in the neighborhood.

Unlike the Rhine, we had to keep going south. We had to get to the Rhône. Like the Rhine, the Rhône begins in the highest peaks of the Swiss Alps, but unlike the Rhine, after leaving Switzerland it flows south through eastern France to the Mediterranean, not far from where the fusion reactor was being built.

We parted company with the Rhine soon after crossing the border into Switzerland, near Basel, where the Rhine valley makes a sudden turn to the east towards its glacial source far from the sound of traffic.

As I watched the Rhine valley disappear into the rear-view mirror, I felt kind of sad. In just our few short days in Germany, I’d developed an affection for the river, an appreciation of the part it played in the story I wanted to tell about Leibniz and England’s German kings and the philosophy of money. The Rhine was there for all of it. People would make their own history. The river just flowed.

To get from the Rhine to the Rhône valley required a trans-basin move. Before there were cars and earth movers, trans-basin moves in mountainous terrain were always the most difficult and dreaded part of any journey. But after leaving Basel, we breezed along on a modern multi-lane expressway. We passed by idyllic Alpine meadows where milk cows coexisted with clover and flowers, just like on a container of “Swiss Miss” hot chocolate mix. Webs of suspended steel got us across bottomless gorges without having to slow down. We breezed through mountains in tunnels towards pinpoints of light like experiencing either birth or death.

I noticed that all the bridges and tunnels were freshly painted, plastered and well-lit, unlike the rusting infrastructure back in America. Of course, neutral Switzerland didn’t have a big army to support like a lazy son-in-law.

I didn’t say anything to Culley Jane or River, but I felt an eerie sense of unreality, like the place was a little too perfect; like there was a place for everything and everything had to be in its place or people would talk; like the internal mechanisms of a wristwatch that you never see but follow without thinking. It all felt too perfectly arranged and polished, like the front lobby of an international investment bank where people go to hide their money.

As we began our descent off the trans-basin divide, in the distance we could see Lake Geneva in the valley of the Rhône.

Time dissolved into non-Euclidean equations.

I saw Culley Jane standing with a friend along the shoreline of Lake Geneva. It was May 1968. She was 19 years old and a student at the University of Lausanne, located on a hill overlooking the lake. It was one of those rare days in everybody’s lives when you realized you're not the same person you were the day before.

Most people don’t know it (I know I didn’t), but the international border between France and Switzerland runs right down the middle of Lake Geneva. Culley Jane and her Swiss friend were standing on the Swiss side of the lake, looking across the waters towards France on the other side.

Her life so far had been a well thought out plan. Middle class… well educated. Her father was a university professor… history. Her mother was a teacher… English. She had two older brothers. She grew up in a nice house in a nice neighborhood in a nice college town in Oregon. They didn’t have a television. They read books at night. An academic path was a given. She chose Pomona College, a prestigious liberal arts school in southern California. She was good with languages. The opportunity to study abroad came along at just the right time. The path ahead was well-marked.

She was 19, an American girl on the Swiss side of the border.

She preferred French literature, but kept up to date with what was going on through the International Herald Tribune.

May 1968.

Back in America, Martin Luther King had just been assassinated. Detroit and Newark were set ablaze. For the first time, humans circled the moon.

Elsewhere in the news, the Tet offensive in Vietnam had erupted into something nobody had apparently seen coming. A generation was being drafted into a war. I was making plans to be in Chicago for the big anti-war rally at the Democrats' National Convention. I wanted Bobby Kennedy, but then he got assassinated too.

In Europe, Andreas Baader, founder of Germany’s militant Baader-Meinhof Group, firebombed a department store in Frankfort to protest what, at his trial, he called “indifference to the genocide in Vietnam.”

In France, which recently had had its own disastrous experience in Vietnam, millions poured into the streets to protest “American imperialism.” They had expected more from America. They were disappointed in America. After WWII, America had helped to rebuild France, not colonize it. Didn’t the people there in America know about Diên Biên Phu, about Algeria? The French said colonial times were over! A national strike was called. Everything shut down. Barricades went up in Paris. Fearing a bloody revolution, President Charles de Gaulle fled the country.

My wife is a self-described introvert and is generally quiet, unless she has something important to say and then there’s no holding her back. Looking across the waters of Lake Geneva towards France when she was 19 years old, she said to her friend: “There’s a REVOLUTION going on over there!”

Her Swiss friend brushed the comment aside with a flip of her wrist. “Oh, that’s just the French. They’re always protesting something or other.”