Thursday's Columns

September 26, 2024

Images of Instability

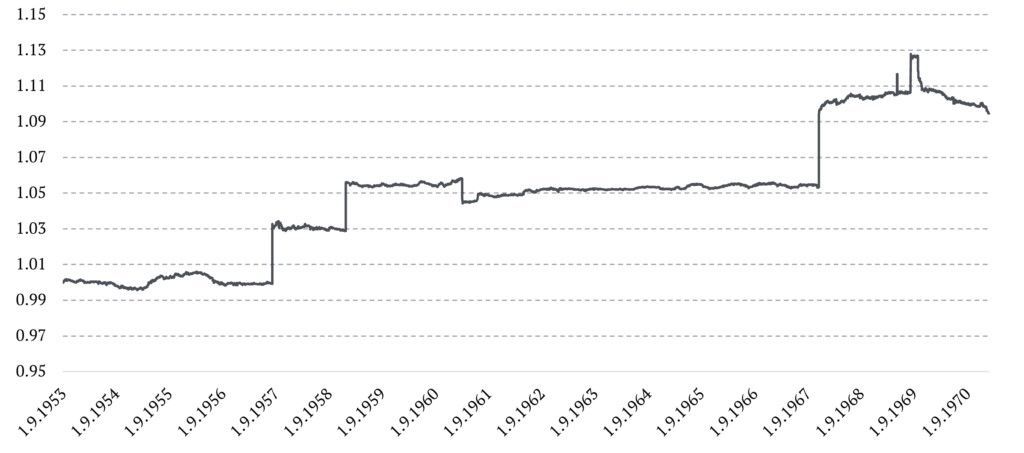

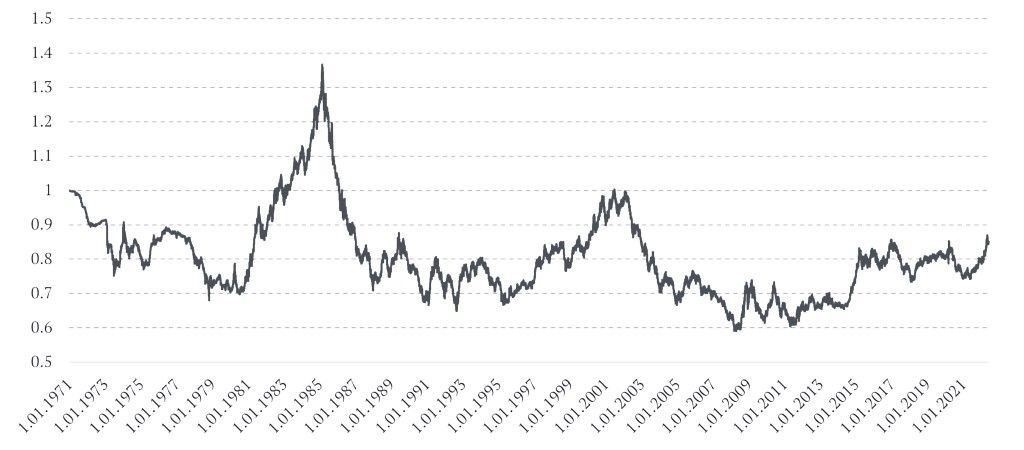

(Dollar Value Index)

Fluctuation of Dollar's value in international exchange compared to basket of major trading nation currencies. (Source: Quaint Econometrics.)

Bretton Woods: 1953-1971

Post-Bretton Woods: 1971 - 2022

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

Resurrection of the Bugs

For this week’s column, I wanted to write about the international monetary system that Nixon threw overboard in 1971, inaugurating what we’ve been living with ever since. Even though my generation had grown up with the previous system in the 50s and 60s, until shortly after 9/11, when I decided to spend the rest of my life writing a book about economics, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as an international monetary system.

I learned that it had a name — Bretton Woods. From National Bureau of Economic Research papers, I learned that it was the third of only four so-called international monetary systems since the late 19th century. Just four. First was the Classic Gold Standard, which collapsed during the early decades of the 20th century, leading to the First World War. Next there was what economists label the Inter-War Period, which was sort of a non-system of cutthroat competition and instability leading to the Second World War. Then came Bretton Woods and after that, since 1971, we’ve been living under what’s called the Post-Bretton Woods System.

So, what was it? What was Bretton Woods? How to describe it in a newspaper column where you have to say in a few words what others write ponderous texts in an occult language to describe? Because I’m an experienced newspaper columnist, I think I can do it. It comes down to “level of imagery.”

The image of Bretton Woods that’s in my mind first came to me close to twenty years ago, maybe around 2008 when peoples’ lifetime savings were being drained to bail out a desperate banking system.

At the time, I was living life as an over-the-road trucker.

In 1939, Vincent Cartwright Vickers wrote a book called “Economic Tribulation.” An Englishman, Oxford-educated economist, heir to the Vickers Armament industrial empire, former member of the Board of Directors of the Bank of England, Vickers wrote while Europe was entering total war. As a bomb maker, himself, in the midst of instability, he was making lots of money, but knew there had to be a better way.

I happened upon the book quite by accident one night while wandering around on the net. I was parked at a truck stop on I-80 in Nebraska. I had been reading lots of dry, technical books about economics at the time, hoping to crack the code. But Vickers’ book was different. It seemed to part an obscuring screen of complexity to reveal something simple on the other side.

Like many economists and international businessmen at the time, Vickers blamed the “economic instabilities” of the Inter-War period for the bombs then falling across Europe and the Orient and had begun to think about a new international monetary system he hoped could be established following the war.

He wrote: "The finance industry, the exchange bankers and the Stock Exchange [i.e. "speculators"] grow rich upon the ups and downs of trade, and are largely dependent on variations and changes of the price levels of commodities [i.e. "instability]. But productive industry grows rich upon stable markets, a constant price level, and the absence of violent economic fluctuations.”

Reading that paragraph lying in the bunk of my truck, it came to me – the “level of imagery” — an image from my very own past; an image from a time when my kids were little and we lived in an old farmhouse on the western High Plains of America.

At the time — the late 80s — after I’d been run out of Detroit, I was running a small-town weekly newspaper in Perkins County, Nebraska, bordering the Colorado state line — “The Grant Tribune-Sentinel,” the only regular newspaper in America to ever endorse Lyndon Larouche for President. He got six votes in the county. (It was rumored that three of them were mine.)

Perkins County is endless fields of wheat and corn with a few small towns huddled around grain silos. On clear moonless nights, the yard lights of scattered farmhouses look like stars in the sky.

The image that came to me the night I started reading Vickers’ book was of a particular species of insect that I’d never seen or heard of before moving to Perkins County. They lived in a secret place. You only saw them after a hail storm had swept through the county, when they would suddenly appear in buzzing swarms to feast on the instability of damaged life.

They were ugly things, green and sickly-yellow with big heads and voracious eyes. Everybody hated them. They had a long Latin scientific name, but everybody in the county just called them “the bugs,” a local epithet with a long local tradition. Old timers told stories about “the bugs” which thrived on the instabilities in the 30s, on the crops weakened by sandstorms and draught. To call somebody “a bug” could cause hard feelings between neighbors. At high school football games, the opposing sides called one another “bugs.” Waving pompons, cheerleaders yelled “squash the bugs!”

Had he lived, Vickers would have been pleased with Bretton Woods. It was designed to squash the bugs.

Nixon, in 1971, with Wall Street/City of London man Kissinger messaging from behind the screen, resurrected them.

A memorable enough image, I think.

Our Latest

Mail from

Eric Chaet

Eric Chaet

All This Analytical Language

I did what I do, time & again, for days & decades

without all this analytical apparatus

I’ve built like a shell around my trajectory —

aggravated, desperate, joyless regimen —

because sometimes someone hit me

for doing what I do —

or withheld an ounce of sympathy or a job

that I damned near needed to survive —

&, I suppose, because of my parents’ anxiety —

it was contagious & I thought it was as natural

as a raindrop, snowflake, worm, sun, leaf

or clouds or cars or stores or English or prices —

& because of what I read in history books

& in the Bible & in newspapers

& because no one even seemed to notice

what they were doing, or why I did what I do.

Eric Chaet