Thursday's Columns

March 7, 2024

The Canals

Two Paths

(Part 4)

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

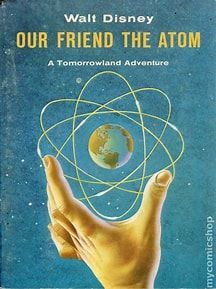

Correction::: Last week I wrote that I first started to think about what an atom was when I was in the fifth grade. But I don't think that's true. I think I was in the second grade when a new book arrived in the school’s science room. The Dominicans read it to us. It was called “Our Friend the Atom.” The following year, Walt Disney made a movie based on the book. Many years later, I learned that it had been part of a CIA operation – “Operation Candor.” The operation had been approved by President Eisenhower during his first year in office, in 1953. Its purpose was to get Americans to think a certain way. Eisenhower wanted people to start thinking differently about the atom. In 1953, people associated the atom with bombs, as shockingly described in John Hersey’s 1947 national bestseller, “Hiroshima.” Eisenhower wanted people to start thinking about atoms as if they were our friends… friendly atoms. A secret National Security Council document declassified in 1983 outlined the way to do it, to rearrange minds. And I quote: “(…) a powerful advertising campaign with billions of individual impressions via newspapers, magazines, radio, TV, house organs, and car cards. (…) Editorial support will also be obtained from newspaper and magazine publishers, editors, and columnists; radio-TV commentators and special program directors; and motion picture producers and exhibitors with trailers and film shorts.”

The opening act of Operation Candor was Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” speech on Dec. 4, 1953.

The idea of using atomic power for peaceful purposes spread across the world like a weather system.

On Dec. 4, 1954 – the one-year anniversary of Eisenhower’s famous speech -- the United Nations General Assembly unanimously approved a resolution to sponsor an “International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy” to be held in Geneva, Switzerland, the following year.

By that time, England had joined America and Russia as one of only three nations possessing atomic bombs, but more than 1,200 delegates from 72 nations attended the conference, which Scientific American headlined as the “Greatest Scientific Conclave of All Time.” The reporter, Robert A. Charpie, wrote: “For two weeks in August, Geneva was the headquarters of the scientific world (…) where scientists freely discussed all phases of the tremendous new field of atomic energy (…) It has become commonplace to see American and Soviet scientists with their heads together vigorously debating the pros and cons of some highly technical point discussed during the Conference.”

More than a thousand scientific papers were submitted containing some of the earliest thoughts about many of the things that today we take for granted, from CAT scans to Dick Tracy watches.

While the majority of papers examined the promise of using the atom to generate electricity, the British Journal of Radiology reported that five of the Proceedings’ 16 volumes “deal with medical applications of isotopes, biological actions of radiations, biochemical and physiological studies, safety precautions and dosimetry.”

But nothing about bombs.

“The Spirit of Geneva,” as it was called at the time, was taking root. Through diplomatic back channels, Eisenhower and Khrushchev were talking. Just ten years earlier they’d been allies in the European war. Their talking would lead to a nuclear test ban treaty in 1958, and for the next three years not a single atomic bomb was exploded on earth – in the atmosphere, underwater, or underground.

Atoms should be used for peace, not explosions.

In 1961, however, the test ban treaty was amended to permit underground testing, which both sides agreed could have “peaceful” applications. They were called “Peaceful Nuclear Explosions,” or PNE’s. They could make big ideas happen by rearranging the lay of the land.

Both the Russians and the Americans had some big ideas.

Russia wanted to change the course of its northern rivers. Instead of "uselessly" flowing north into the Arctic Ocean, they wanted to divert them southward onto the vast arid lands of Central Asia for irrigation and development and to replenish the shrinking Aral and Caspian Seas. It was one of Khrushchev’s big dream projects, like orbiting a satellite, or Eisenhower’s Interstate System. Russians called it their “Great Northern Rivers Project.”

America had a big idea in mind, too, a sea-level shipping canal from the Mediterranean to the Gulf of Aqaba through lands granted to the Jewish people by the United Nations in 1948 – the year I was born.

The Russians made no secret of their big idea. Khrushchev was always boasting about it and it was big news in Russia. When he was in Disneyland I can imagine him thinking that if America could build something like this, Russians could change the course of rivers.

America, however, stamped its plan Classified and secreted it away for thirty years.

The Russian plan was geoengineering.

The American plan was geopolitical.

(to be continued…)