Thursday's Columns

March 27, 2025

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

Detroit, 1979.

Benjamin T Profante, known as Benny, was on a new case. Or, as the Blues Brothers might put it: “On a Mission from God.”

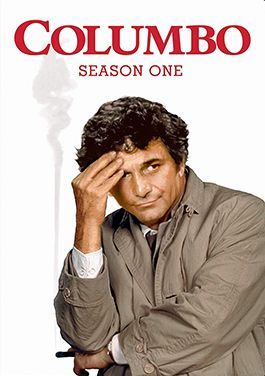

Benny was good at imagining himself as somebody else. In his rumpled coat and hung-over mind, he imagined that he was Columbo.

He moved cautiously down a dark and dreary hallway of an old downtown hotel built for another age, looking for room 666 on the 6th floor to meet with somebody who was said to have information.

The old hotel’s worn wood flooring creaked and groaned beneath his every careful step… sounds from behind locked doors… naked electric light bulbs dangling from the ceiling at the end of cobweb-coated cords.

Detroit.

1979.

By 1979, Detroit was becoming a dark and dreary place.

When a mist blew in off Lake St. Clair, in some neighborhoods that had not long before been neat rows of brick middle class housing with kept-up lawns and kids running around in the street, the feeling could be ghostly, like the emptiness after a nuclear war.

Detroit was not turning out the way everybody thought it should. It was supposed to be the shining light of a nation’s progress and prosperity, harnessing nature through science and technology, planning and organization. It’s where Rosie the Riveter had worked to defeat an idea called Fascism. It was the beacon that drew a great migration of oppressed peoples from America’s South. The East Coast had its international bankers and the West Coast had its oriental trade and orchards, but America had Detroit, churning it out.

Detroit was nature’s primal urge to take off, to see something new. Like it had been part of the plan all along — an inviting, temperate place on earth with navigable waters, forests for shelter and fields for fruit and corn. Like a living organism adapted perfectly to its surroundings, Detroit was at the hub of a great productive region created by nature to facilitate motion… motion, ceaseless motion; a machine transforming hydrocarbons created by green leaves into the mechanical motion of steel pistons turning gears. It transformed the mystery of “energy” into a kind of “civilization” with Main Streets and parks and movie theatres on a planet in a mystery called “space.”

Detroit was an idea, a morphogenic idea, and the idea spread throughout the region. It was at the center of economic circles of lives lived by regular people going to work at regular jobs in regular towns with neighborhoods where everybody knew one-another’s name.

From coal mining towns in West Virginia, southern Illinois and Kentucky to the mining towns of the iron-rich Mesabi Range along the southern shores of Lake Superior, people huddled around industrial plants — not just the massive Willow Run and Rouge plants of Detroit, but countless Midwest towns where parts of the whole were made… piston rings, brake shoes… and the truckers on the highways and the seamen on the Great Lakes moving all the stuff around.

It was a system — an economic system — that Benny knew by heart. He had lived it. It was as familiar to him as the taste of salt.

In the small town at the edge of the woods where he’d grown up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, his French-Canadian great-grandfather had worked in the Ford plant there where the wooden bodies for Model A’s were made. His Swedish grandfather ran logging operations, supplying the raw timber. During WWII, the plant was re-tooled to produce the wooden gliders used on D-Day.

The system Benny knew had defeated the idea of Fascism, and then we went to the moon.

But by 1979, we had stopped going to the moon, and Detroit was becoming a dark and dreary place.

What had happened?

By 1979, Benny was a newspaper reporter. It was his job to find things out, and he wanted to do a good job. Even when he was hung over bad from the night before, he always wanted to do a good job.

The first thing he’d learned as a rookie reporter back at the beginning of the 70s was that every story has a Who, What, When, Where and Why — the 5W’s.

He knew the What right away in an instant without hardly thinking about it. It was perfectly obvious. It was what he saw with his eyes wide open. It was written on the city’s face and in the history of the decade when we’d stopped going to the moon.

So he had the What and with a little digging it didn’t take him long to get the Who, When and Where. But he would spend the rest of his life trying to get at the Why. That was the toughest part because it required self-awareness — Why do we do What we do? What motivates us? How do we process guilt?

To catch the guilty party, Colombo had to imagine that he was that somebody else, seeing with their eyes, their motivations, the way they processed guilt. It can be an unpleasant experience, but Colombo wanted to do a good job.