Thursday's Columns

September 28, 2023

>>>>>>>>>>

Preface: An Email from an Old Friend

The first thing I told the cop about the thief who robbed me in a parking lot last week was that he was a young black guy. I thought about it later. Did that make me a racist, that that was the first thing I noticed? Was I not who I thought I was? Something other? It was something I thought I should think about. Some people meditate or pray to untangle thought knots. I write. I wanted to write about identity; about why we think we are who we think we are and how that effects the direction of our steps, like a morphogenic idea. I thought about it, but at the time I had something else on my mind.

A couple weeks ago, I wrote in this column that I had decided to quit writing; that it had been a difficult and emotional decision; that it was like saying farewell to an old friend at a funeral, never to be seen again at this wavelength.

Then I got an email from Eric Chaet. After reading my column, he wrote me:

=====

Old Friend:

What was your motive, when you began writing?

Is that motive still alive? Same degree? Among other motives, which have come into effect? How strong is it, how strong are they? What would you like to achieve, yet, if you can? How feasible? Is writing part of achieving it? Are you just discouraged by lack of effect? What could you have been doing that wouldn't have caused you to feel discouraged by lack of effect? How can you have greater effect, by writing or otherwise? What effect? How much effect, sanely, to hope for, from writing or otherwise?

You don't want to discard a skill that you have developed, just because you are temporarily discouraged, or because your body, having aged, is tired in new ways. Or do you?

Do you have a new motive you haven't recognized yet, & is writing a reasonable part of it?

Is writing the issue? Or, rather, is it that ANYTHING doesn't seem worth the effort. Or, rather, other things seem easier. Do the easier things lead to what you yet desire more or less than writing?

When you write, if you write again, why? For whom? Writing is never the thing. Writing is a way toward effects, good or bad, trivial or profound, soon or later. So is going for groceries. So is informing yourself. So is improving relationships, or not. Etc.

I’m rooting for you:

Eric

====

<<<<<<<<<<

Our Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

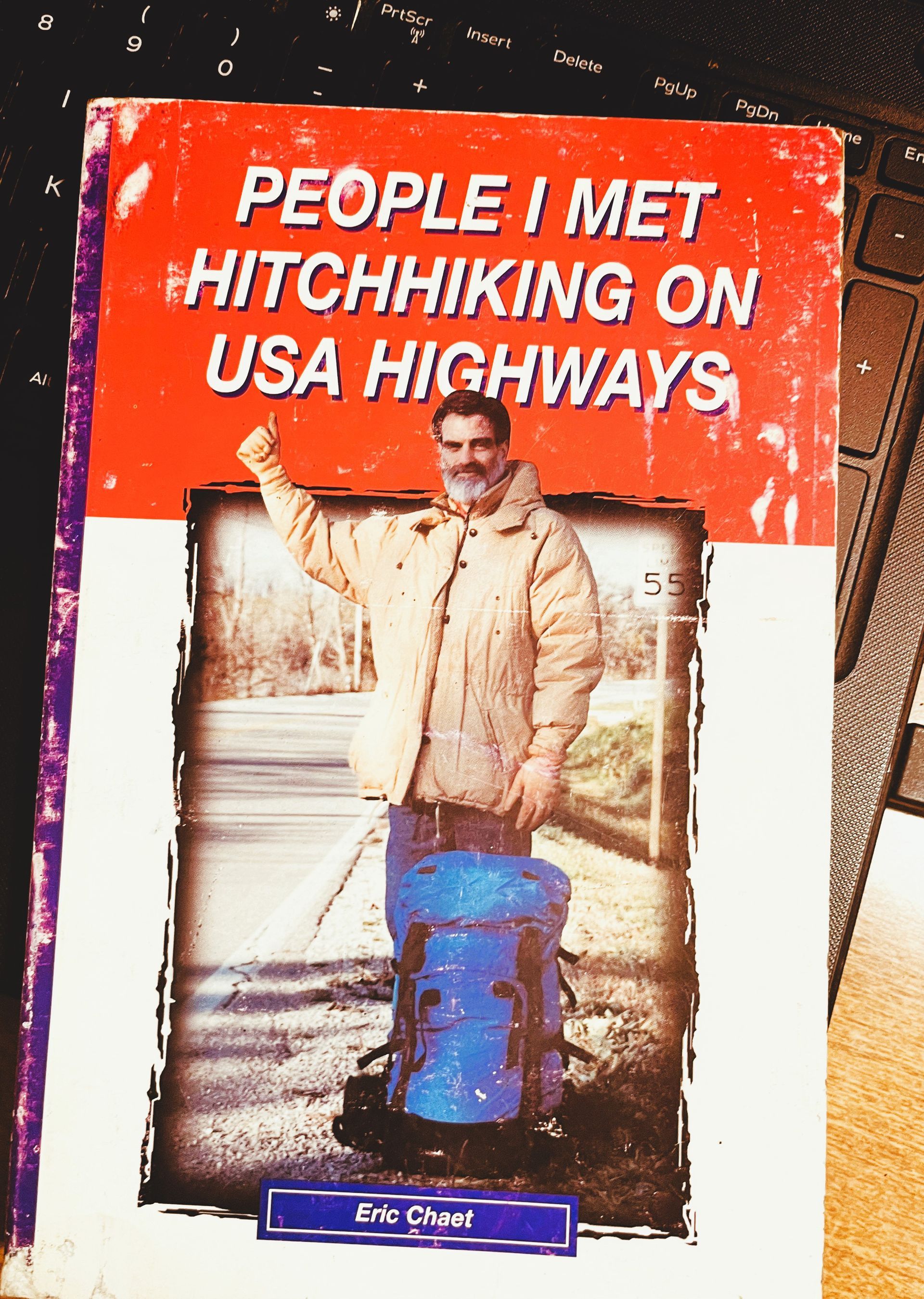

Cover of one of Eric Chaet's later books, published in 2001. It's on our bookshelf of classics here in the Westphalia library. You can contact us about obtaining rare copies of all his works. You can trust Westphalia to recognize what's classic. They're pricey, but under any reasonable system of justice he deserves a living. He still works his garden, but he's getting old. He lives in northern Wisconsin. Winter's coming.

Eric and Me

Chapter One

I first met Eric Chaet in 1976. I met him in Marquette, a college town on the southern shore of Lake Superior in Michigan’s “Upper Peninsula,” where Yoopers live. I think he was in town to be interviewed on the local radio station about a book he had just published. He was just getting started after growing up on the tough side of South Chicago, but over the coming years applause for his works would issue forth from a diversity of crowds, from Ferlinghetti's San Francisco "Beat" circles to Ed Asner, who played Lou Grant on the Mary Tyler Moore Show. His words would be translated into over a dozen languages. But in 1976, I didn’t know anything about him, or about the radio interview. I didn’t have a radio. Actually, I didn’t have much of anything that I couldn’t fit into a backpack.

At the time, I was living in a square room on the fourth floor of an old hotel by the railroad yards; a single naked light bulb dangled from the ceiling at the end of a cobweb-coated cord; bathroom and shower down the hall.

The room’s one window had a great view of Lake Superior as it trailed off before disappearing into the northern horizon. At night, out back on the rusty wrought iron fire escape clinging to the building’s weathered bricks by fingernails and teeth, I shared bottles of MD 20-20 with Depression Era hoboes who’d never been able to settle down and wound up in this place, alone with their stories, waiting for somebody to tell.

First thing after I got there, after unpacking my backpack and laying my things out on the floor, even before I showered, I went to the local St. Vincent DePaul second-hand store and walked out with a vintage Smith-Corona black manual typewriter, like the kind we had in Mrs. Ochetti’s typing class in high school, and even at the first newspaper where I worked. I also made sure to pick up two extra ribbons. My Great American Novel was going to be a long book.

I placed the typewriter on the table in front of the window, just so. Next to it, I arranged a neat stack of empty sheets of clean white paper. I carefully rolled the first sheet into the machine’s black rubber carriage. Even though I hadn’t been in a church since I’d first started thinking and doing things I didn’t want to confess, it felt like a Catholic act. Ritualistic. Certainly a memorable moment. Someday, after I was famous, the sheet of paper on which I wrote the first words of my Great American Novel would be worth a fortune at auction, benefiting my heirs, like owning the sheet of paper on which Steinbeck first scribbled: “In the town they tell the story of the great pearl -- how it was found and how it was lost again.”

The sun went down. Through the window in front of me, I watched a multi-colored curtain of shimmering Northern Lights rise up like kettle steam from the frigid depths of a great body of water that had been created in the wake of a passing glacier, receding to make room for people. I heard a clacking sound bouncing back and forth off the walls of my room, like a team of iron-shoed war horses coming down a cobblestone street. A whirlwind of sheets of ink-spotted paper started flying out of the old Smith Carona, floating in the air, suspended like debris in space. I didn't know what was going on. I didn't know what I was doing. I was 27 years old and lost. But I didn’t know I was lost. So I just kept going.

The worst thing about being lost is when you don’t know you’re lost. You’re stumbling around where nothing is familiar and the exit could be anywhere. Growing up in a small town at the edge of the woods, we were taught early on what to do if we ever got lost in the woods. You do the obvious. You stop and build a fire. Somebody will come to get you. Don’t worry.

But if you don’t know you’re lost you'll just keep going, racing through the needles of cutting underbrush towards a gravel road you’re sure is in one of the directions. Come morning, they’ll find you at the foot of a granite outcropping. Dead. Your skin and clothes torn to shreds.

Sometimes we figure it out for ourselves and sometimes it helps to have somebody around we trust, like my wife the professor, Culley Jane, who lets me know when she thinks I'm lost.

That’s how Eric Chaet arrived on the stage of Our Story, a long time ago, in 1976, along the southern shore of Lake Superior.

(To be continued…)