Thursday's Columns

August 17, 2023

Our Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

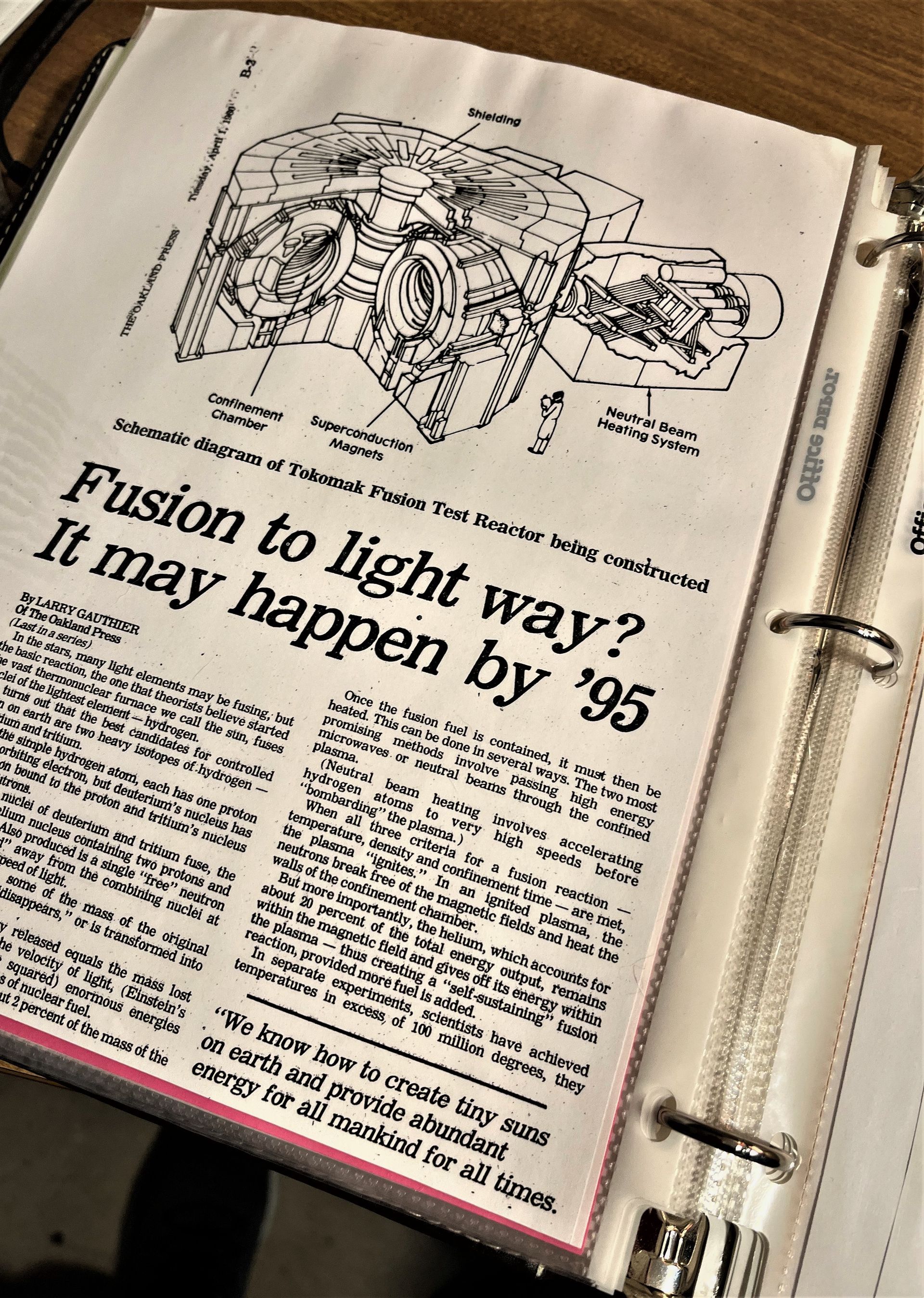

Old clipping from the 1980 fusion series.

The "'95" meant 1995, not 2095.

Americans in Europe

(Part 10)

Zipping along the highway at 115 kilometers (not miles) per hour I felt like a voyager going from the past into the future. I didn’t want to miss the scenery along the way, but my mind was wandering.

River was asleep in the backseat of our rented VW Golf. Culley Jane was on her iPhone with the GPS lady, navigating our way in the Rhine Valley from Germany to France.

I paid close attention to the road and the traffic. As an old trucker, I know you can tell a lot about a place by the way people drive. Out on the German expressway, people seemed to be going about their business in an orderly way. It felt civilized… not a lot of sudden moves, bobbing and weaving in and out of lanes to gain an undeserved advantage. I merged into the flow of it and was comfortable. There were no billboards. Over-the-road truckers had their own lanes. The sky was clear. The road was smooth.

We were passing through a postcard scene of German villages, farms, church steeples and factories off in the distance.

That’s when the feeling first struck me… the feeling that I was like traveling from the past into the future.

Germany had drawn me into the past and to what had already happened.

France was drawing me into the future and to what could possibly be.

The future was in southern France where the world’s biggest fusion reactor was being constructed and I was on my way to see it and to take pictures like a photojournalist on international assignment.

When first presented with the idea of going to Europe, I said I wanted to do two things: First, take a picture in Westphalia where the 30 Years War was finally resolved; and, Second, take a picture at the ITER construction site in southern France. I especially wanted River to experience how far we’d already come and to see what was possible. It was Leibniz, himself, who said that whatever is possible demands to exist.

I also wanted to remind myself.

The acronym, ITER, stands for “International Test Experimental Reactor.” It’s going to be the biggest fusion reactor the world has ever seen. It’s where a star will be born, like having our very own sun to take along with us wherever we decide to go.

We first started creating tiny suns on earth over a Pacific atoll in 1952. They were awesome displays of the energy contained within a subatomic particle. When I see old pictures or newsreels of hydrogen bomb explosions -- mushroom cloud rising towards the stratosphere -- I imagine that I’m looking inside a tiniest thing -- a proton. To what it’s made of… energy. E=mc2.

But bombs are like the neighborhood’s feral cat – beyond our control. But we had discovered ways to trap it and were now domesticating it to produce, as was expressed in the Fusion Energy Act of 1980, “an inexhaustible supply of safe, clean, affordable energy for all mankind for all time.”

Like when you wake up in the morning… if you’ve got the energy, you can do anything. You might even decide to make it your money. (Culley Jane questioned this money allusion, but I decided to leave it in because it makes sense to me… l.g.)

The ITER project is the biggest scientific project ever undertaken by the people of Earth. All the big countries are involved and already positive results are being achieved, even before the machine is fired up for the first time. For instance, even though Russians and Europeans are at war again, they’re still both cooperating members of the ITER project. (In the opinion of this reporter, it’s a benefit of science you don’t hear enough talk about.)

I first heard about fusion in 1980 when I was a newspaper reporter in the Detroit area. I remember the year because it was the year Reagan was elected and Detroit was getting rusty, like the bones of an aging generation.

During the 20th century, Detroit had emerged in the nation as the hub of a regional conversion process whereby America’s industrial Midwest would convert a mysterious something called “energy” into mechanical motion -- muscle cars; four-on-the-floor GTO’s; “Super Sport” hemis and Sting Rays -- and family cars for big families… the Bonneville and Fairlane and station wagons. A generation learned how to swim without breathing in the backseat of the old man’s Chevy where there was room to roam. We couldn’t get enough of it and Detroit kept churning it out, an industrial army covering three shifts at the local factory. Kids watched “The Jetsons.” Flying cars. Why not?

So when word started getting around that the world was running out of energy, it was big news, especially in Detroit.

The signs of it were everywhere in the 70s -- the oil embargoes, long lines and high prices at the pump, experts under oath with charts before Congressional hearings explaining Peak Oil, that there were too many people asking for too much, that we were running out and that if we didn’t change our ways everybody would die.

The story first gained real legs in the early 70s after the Club of Rome published the results of its “Limits to Growth” study. One of the world’s most advanced computers at the time, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had been asked a simple question: “Where will we be in fifty years if we keep doing what we’re doing?”

The computer digested the data and spit out an answer. It was not encouraging. At the time, we were still hitting golf balls on the moon and thinking about the next step in the journey, but the computer said there were limits to growth. Like a street corner evangelical with an important message to proclaim, the computer said the End was Near. Food, land and resources, in general, and energy, in particular, were finite and obviously human nature was not going to change.

In a word, the study concluded that Malthus was right.

Thousands of privately funded think tanks scattered across the ideological landscape are always trying to get their story onto the front page of a newspaper. City editors get swamped with their press releases. Most all of them wind up in the trash or on a back page. But because the Club of Rome was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and held its meetings at the Rockefeller’s palatial estate in Bellagio, Italy, the results of its study were broadcast to the world, first, on the front page of the New York Times, and then by Cronkite and the AP wires.

Over the course of the coming decade, austerity, or making do with less, grew rapidly as a cultural ethic. It became one of the things parents tried to teach their children. The storybooks became less about journeys into the unknown and more about stopping to smell the flowers.

To survive, you couldn’t be driving all over the place in a big car.

Consumers flocked to fuel efficient Japanese imports.

Detroit’s giant assembly plants and parts factories at the heart of small towns scattered throughout the Midwest started closing their doors. The End was Near. You could smell it. Iron oxides. Rust. All because of “the news.”

The “News” called it the “Energy Crisis,” which pretty well summed it up. Squeeze energy out of a system, and you’ll have a crisis. The political system responded. A national “Energy Czar" was appointed. The Interstate speed limit was lowered to 55. Money was made more unaffordable to slow everything down.

Reporters in the newsroom chased after the story in all its manifestations, from fistfights in the lines at the gas pump to the touching story of a young couple expecting their second who learn the Pontiac Motors plant is going to close. Any story with an “Energy Crisis” angle was sure to get front page play.

I was actually working on a different story when I first heard about fusion. During the time I’d spent on the Hoffa case I got to know lots of Teamsters who had known him or knew people who had -- dock and warehouse workers, chauffeurs, long haul truckers. I was working on a series of stories about the political intrigues and infighting going on inside the union now that Hoffa was gone.

One night I was drinking a beer with one of the Teamsters I had gotten to know and he got to complaining about the cost of diesel for his truck. “It’s all bullshit, you know,” he said, ordering shots. “The whole ‘Energy Crisis’ thing… it’s all made-up bullshit.”

I asked him what made him say that.

He said he’d heard it from another guy who’d heard it from somebody else who’d heard it somewhere. Maybe at an airport.

Over the next couple of weeks I tracked his story down.

I quickly found myself in an unfamiliar world of plasma physics and quantum leaps where things don’t have to be the way they appear to be. The scientists there (including Nobel laureates) said that, no, we were not running out.

That’s when I first learned about fusion.

I wrote a series of stories about it.

They were hard stories to write because I had to explain what fusion was, and I was just starting to learn myself. And then I had to translate the interviews into the vernacular.

Everybody knew it was a sensitive story and that we had to be careful. It challenged a powerful idea and its powerful backers. The physicists and engineers and politicians I interviewed for the series were careful to never come right out and say things like: “The Energy Crisis is a made-up Hoax.”

It was all in code.

They just laid out what was possible.

It would be up to the people to read between the lines.

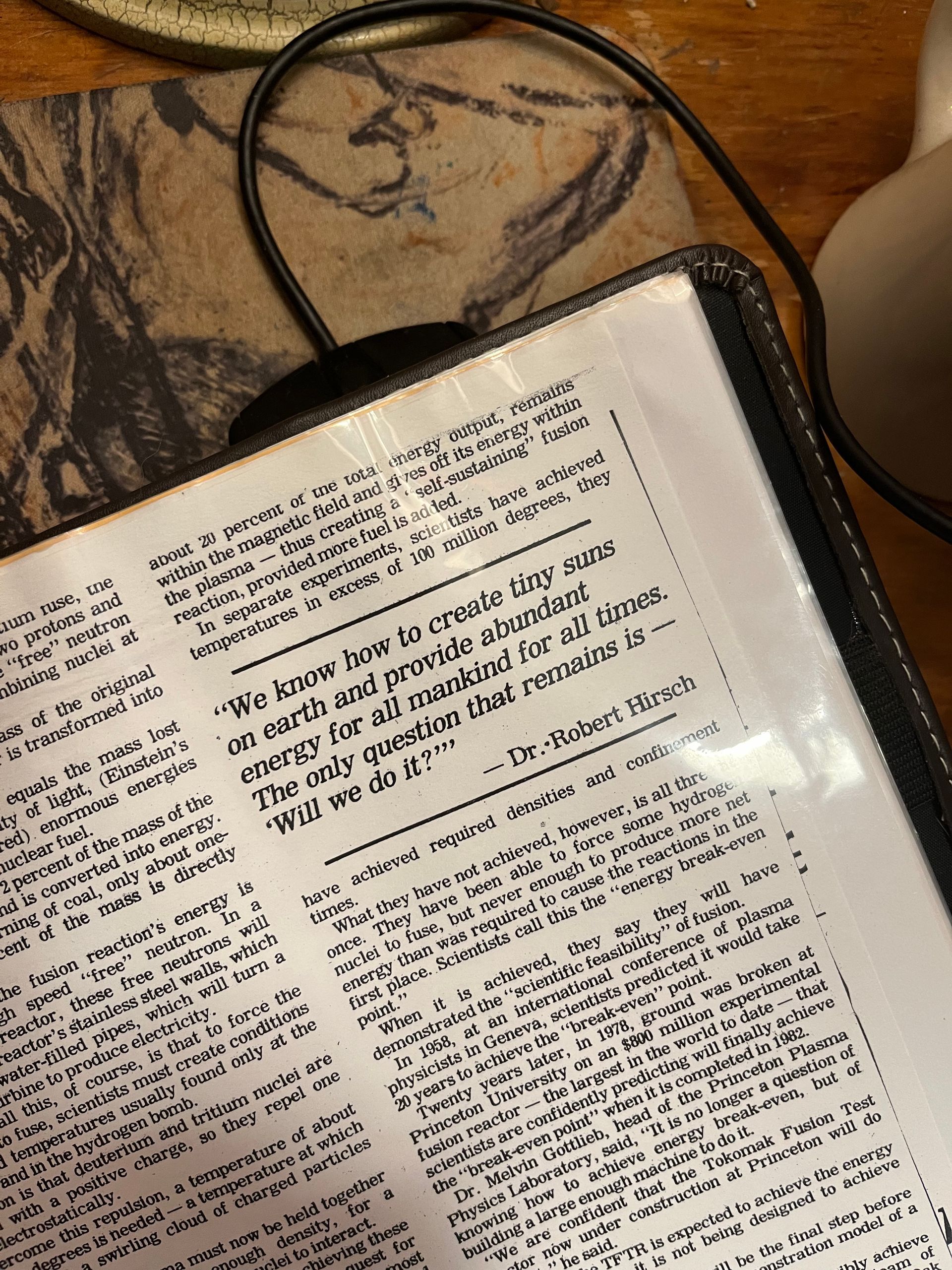

Highlighted from 1980 interview with Dr. Robert Hirsch, director of the fusion energy division of the Atomic Energy Commission.