Thursday's Columns

June 27, 2024

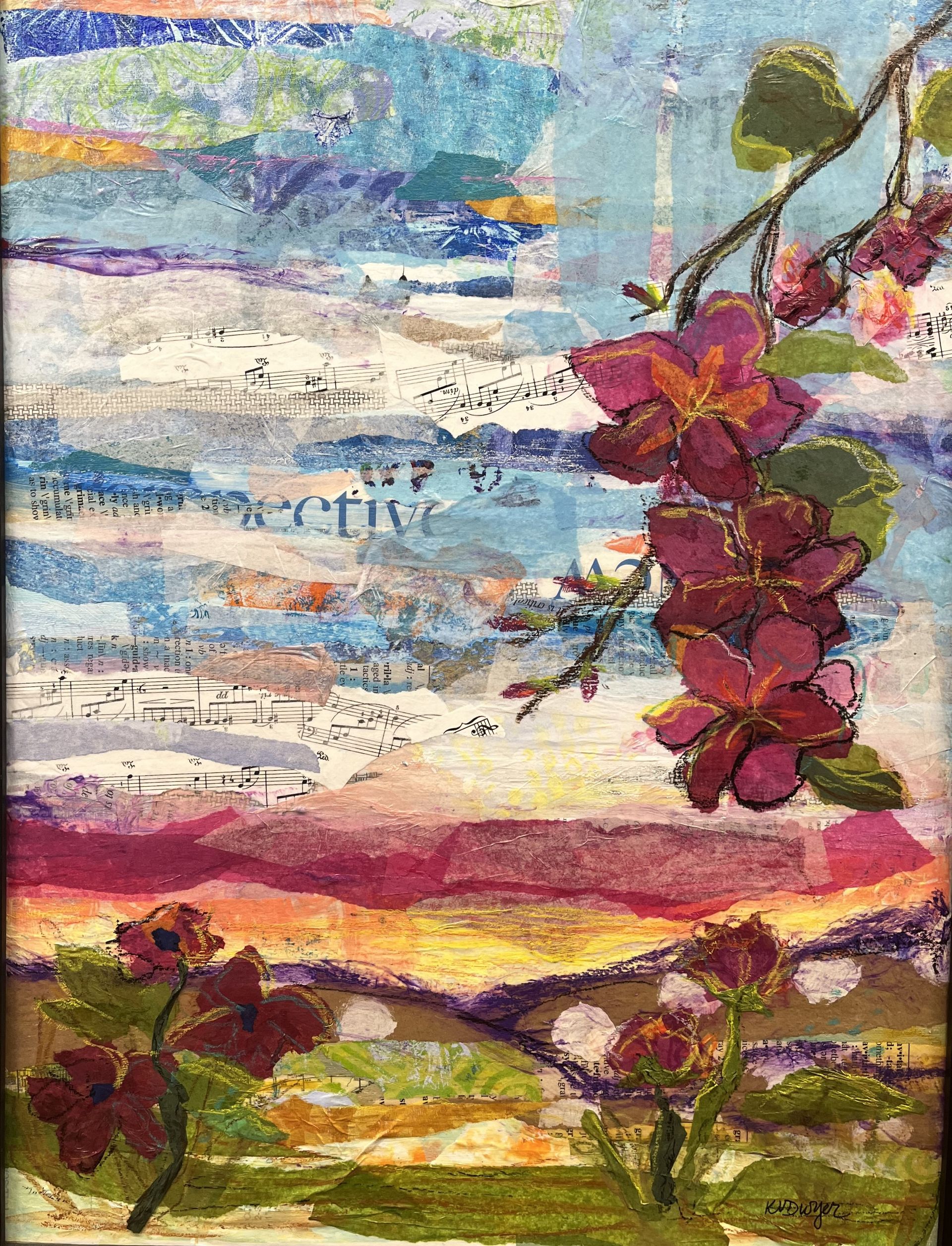

New Perspectives

Our

Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

Kim

The Story of a Painting

(Part 3: The End)

In his late 19th century “Treatise on Literature,” Schopenhauer wrote that no matter what we do – be it doing the dishes, making love, raking the leaves, or whatever – that it will be a perfect reflection of who we are.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in the lives lived by famous writers before they were famous; why I can’t look at a creation without wondering about its creator, be it a painting, or a building, or a patchwork of fields of wheat out on the High Plains of America created by somebody who grew up on a farm and took 4-H in high school. Our creations are always the story of a life in a kind of code.

And, lucky me, I was getting to do a newspaper interview with the creator of a painting that had caught my attention at a local art show. Like having a beer with Kerouac before “On the Road” made him famous.

There’s a structure to the art of conducting a newspaper interview. I learned how to do it from Jake. Jake was a crusty old goat who kept a bottle of Kessler’s in his desk drawer. He was the city editor at the first newspaper I ever worked at, back in 1970.

Jake had gotten his start in Chicago in the days of Capone. After he started getting old he tried to retire, but it didn’t work, so he took an opening at a small town daily on the Michigan/Indiana border. That’s when I arrived. His job was to teach me how to be a newspaper reporter.

“The first thing is the interview,” he said to me on my first day on the job. “Always start with three questions: ‘Where ya from? Wha’d yer ol’ man do? What’s yer line o’ work?”

Jake had his own way of talking, but the message stuck.

Sitting across from one another at a long folding table on folding chairs in the emptied reception room of the Heritage Fine Arts Guild’s annual awards show, I quickly learned that the creator of “New Perspectives” had grown up in lots of different places – rural Illinois, Connecticut, Europe and then back to Connecticut where she finished high school in the late 80s.

I learned that her father was an engineer and that, yes, the man she had been standing next to out in the crowded room was, in fact, her husband. They had met in college. They both had careers. They had three sons.

She said her name was Kim. She said as a child she could entertain herself for hours with crafts, paint-by-numbers and making things with her hands. Her grandfather and great-grandfather had both been artists. Their paintings hung on the walls of her family’s homes. Even when her father’s work took them to Belgium, where she spent most of her high school years, her grandfathers’ paintings were packed up and taken along.

She took art classes in high school and in college. She thought about pursuing a career in art, but the uncertainties of that path didn’t appeal to her, the life of a starving artist. As Jake would have put it, she decided to go into a different “line o’ work.”

So Kim became Dr. Kim Dwyer, a PhD clinical psychologist. Her husband, Jerry, is a PhD clinical psychologist, too.

At first I was struck by a scary thought. Maybe she was talking to me just because she thought I needed psychiatric help. “Nah,” I thought to myself, “she looks too happy.” But that part of her life would be there in the painting, too, just as Schopenhauer said. Self-help books say when you go home at night you should leave your work behind you back at the office, but easier said than done. Her work was private and cloistered behind the walls of strictest confidence. It could only come out as code.

We didn’t get into the details, but I felt safe assuming that the 90s and the opening decades of the 21st century had been a busy time for Kim -- at home, raising a family; at work, building a successful private practice. Little time for “art.” Maybe she painted some walls in the house, but that was about it.

But then about eight years ago for complex reasons she decided to once again put brush to canvas. Colors without names and vaguely defined shapes came out of her. She looked at it, shook her head and stashed it away in a drawer to be forgotten.

But then during Covid she took a class to learn about the techniques of collage.

She got an idea.

She retrieved the old painting of amorphous shapes. Into it she wove strips of musical notation and cursive script and dreamy scenes of embryonic human habitation deep in the background that I’d taken for a post office with Benjamin Franklin coming out the front door waving and asking me my name. Reason transformed amorphous clouds of color into lives lived on a planet in space with laws and dreams of what's possible.

Leibniz wrote that whatever is possible demands to exist.

If we don’t know what’s possible, we’re lost.

Once the masks came off after Covid, Kim started exhibiting her art in shows around Colorado where many fine artists live.

“This is the first time I’ve received any recognition,” she said with a wide, satisfied smile, like she’d made it across a finish line.

“It’s my painting, too,” I said.

“I’m glad,” she said. “It’s what I had hoped to accomplish.”

(THE END)

Husband, Jerry, with Kim, holding her yellow ribbon.