Thursday's Columns

December 7, 2023

Our Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

Inspiration Everywhere

Zen Writing

A Zen guy on the road once told me that there’s a time to write and a time to write and that it was important to know the difference.

My favorite writing trick when I don’t want to write is to write about not wanting to write.

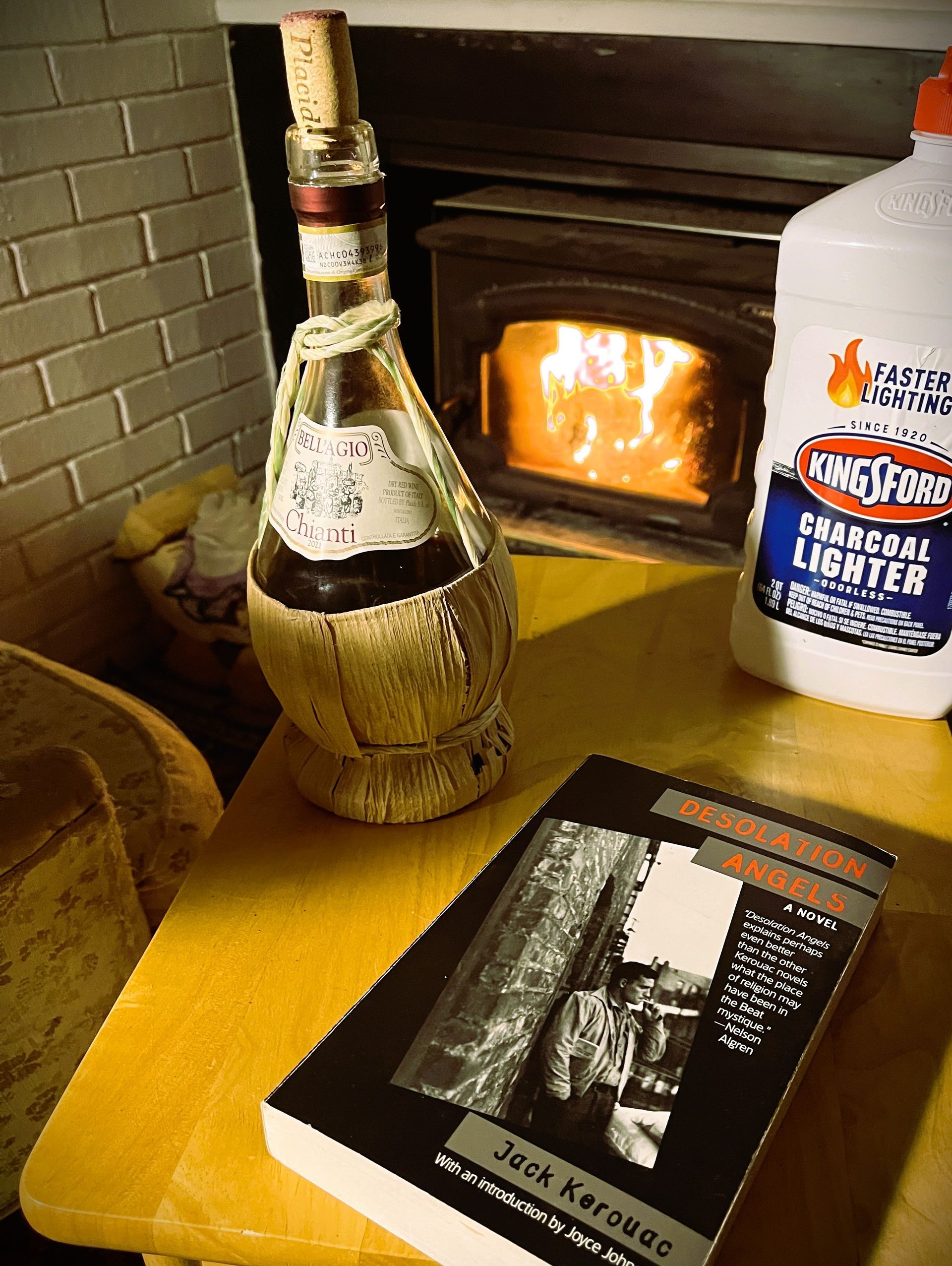

It was Sunday, the first Sunday following Black Friday, 2023. I’d had my coffee and I didn’t want to write or go anywhere. We’d been avoiding the holiday crowds. I’d never been to a Black Friday event before. I’d read about them over the years and thought it might be interesting to see for myself. I wanted to park the car and hang out in the Walmart parking lot. Maybe there’d be a riot and I’d have something to write about. Instead, my wife the professor, Culley Jane, and I stayed home and watched a French movie with English subtitles. French movies are my favorite. They’re philosophical, expressing existence in the silence between words… An old couple. A wood table. Eating soup with spoons. The next day I just putzed around in the yard and in the garage and baked an apple pie and walked around the park behind our house with my wife. Then it was Sunday, which is usually a good day to write, but I didn’t want to write. A light snow was on the ground. I made a fire in the fireplace. I cheat. I use Kingsford charcoal lighter fluid instead of paper and kindling. I have nothing to prove. I could start a fire with fish bones on a frozen northern lake if I had to to survive. I know how to make a fire without cheating. I grew up in a small town at the edge of the northern woods. Dad read Jack London’s "To Build a Fire” to us when we were young. I know how to do it. I could use Kingsford charcoal lighter fluid if I wanted to. I grew up in Iron Mountain, next to Kingsford where the Kingsford charcoal company got started. I could write about Kingsford, way up north in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Early in the century, Henry Ford built a sprawling production complex there. The first generations of Ford models required lots of wood and the U.P. was a virtually untapped source of virgin timber. During the war, the plant produced the wooden gliders used during the Normandy invasion. Thousands of tons of sawdust and scrap wood accumulated until a chemist at the University of Oregon came up with an efficient industrial process to turn the mountains of waste into charcoal briquettes. The war ended. Like the people today storming our southern border, young families fled crowded cities to suburban homes with backyards and a patio with a charcoal grill for weekend parties. By the 1950s, when I was growing up just a bike ride away from the Kingsford charcoal plant, 80 percent of all the charcoal briquettes used in America came from there. Not long after the war, as aluminum began replacing wood, the giant Ford plant in the northern woods where Model A’s and then combat gliders had been built finally closed its doors. But the Clorox Company, which owned and ran the adjoining charcoal plant, could see the future and had big plans... national advertising campaigns, promotional placement in Hollywood movies, expanding the product line to include Kingsford brand charcoal lighter fluid. My great-grandfather Thibault was a foreman in the old Ford plant and knew everybody in the charcoal plant. Everybody in town knew the Thibaults. His side of the family had come directly from France and not through Canada. As I was growing up in the 50s, Monseigneur Pelisieur still heard his Confessions in French. My dad told us the story about the only time he ever saw his grandfather cry. He saw him sitting in his favorite living room chair next to the radio, listening to the news. France had just surrendered. And he cried.

I could write about Grandpa Thibault, but I didn’t want to write.

The day passed, the first Sunday following Black Friday, far from the sounds of an anxious crowd.

The sun went down.

It was going to be a cold night. I went to the store where an Italian chianti caught my eye. It was from Bellagio, Italy. I know about Bellagio, about the Rockefeller estate there, its high walls and tight security. It was where initiated social engineers met during the late 60s and into the 70s to formulate a new international monetary system and then explain why everybody would have to do with less.

I went back home. Culley Jane was almost asleep. I wasn’t tired. I went downstairs. The sudden flash of a kitchen match. Fresh wood. A little Kingsford charcoal lighter fluid and soon the fire roared.

Sitting in my favorite thinking chair in front of the fire next to a table with energies distilled from trees and grapes and the mind of a Zen guy on the road, I knew that it was time to write.