Thursday's Columns

June 22, 2023

Our Story

by Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

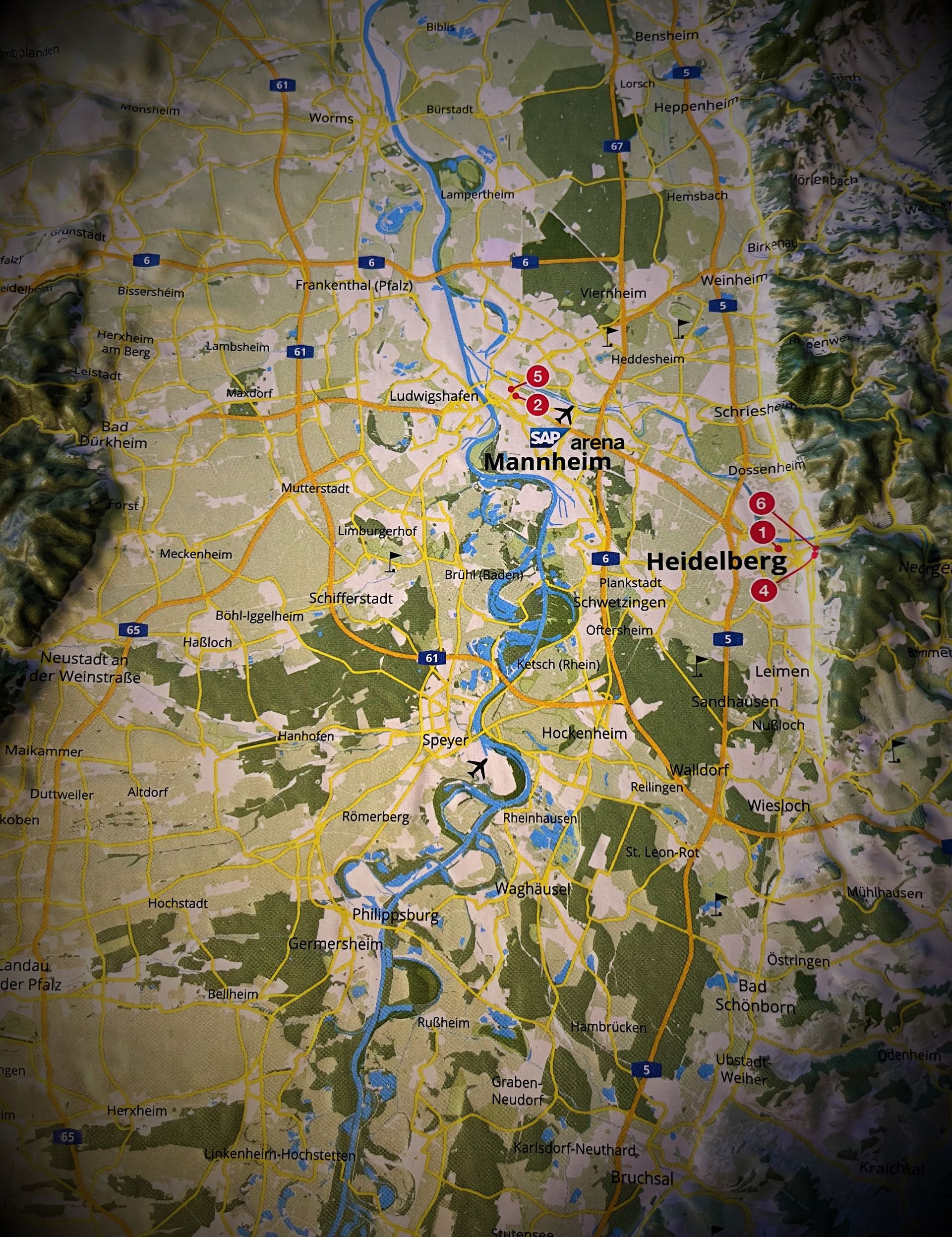

The Rhine-Neckar Region of southern Germany, once the center of the historic Rhenish Palatinate.

Americans in Europe (Part 2)

Heidelberg, where we woke up jet lagged the morning of our first day in Europe, is nestled up against the ridge of mountains defining the eastern boundary of the wide, fertile Rhine Valley in southern Germany near its historic border with France.

Westphalia, where I wanted to go, was over there, maybe fifty miles away to the west, on the other side of the ridge of mountains defining the valley’s western boundary. To get there, we would have to get across the Rhine and its valley, historically known as the Rhenish Palatinate. For many centuries before German unification in the late 19th century, the area was ruled by a long line of kings connected to the dynastic Wittelsbach family. It was productive land, well-watered and flat, desired by all who had the power to extract taxes from the people. A few times a French king or a Napoleon took a piece of the pie but were always beaten back by shifting coalitions of German princes related by birth or marriage to the Wittelsbach’s. By the 18th century, many of the locals had had it with all the wars and moved to America, where they become known as Pennsylvania’s Dutch (or Deutsch) and played a role in founding a new country, in many ways unlike the old.

Before we got to Europe and I started looking at detailed maps, I always thought Westphalia was a German town. But it’s not, just like “out west” is not a town in America. Westphalia, where I wanted to go, was an area, not defined by the physical features of rivers and deserts, but by an idea in the minds of the people.

And it was “over there.”

We didn’t have a tour guide, but our lodging had a great shower and we had our rented car, pockets full of Euros, maps and time. Culley Jane was in communication with the navigation lady on her iPhone. River was in a comfortable outfit, anxious to actually see a world she’d read about in school.

I wanted to visit Westphalia for lots of reasons. For one, I wanted to get a photograph of some kind of roadside sign there that said something like “Welcome to Westphalia,” maybe to use in a Westphalia Publishing logo. For another, I wanted to visit my roots. Not that my family had any genealogical connections to the area. My European ancestors came from France and Sweden. I wasn’t seeking the nostalgia of revisiting my own personal past, like going back to the industrial valley in Milwaukee where I was born and spent my initial years, my earliest memories of the smell of breweries and meat packing plants. Not that. I wanted to experience a different kind of roots… intellectual roots… Westphalia, birthplace of an idea I still believed in with the conviction of a Dominican nun. An idea that stopped the killing.

Heidelberg, the historic capital of the Rhenish Palatinate, had arguably been the birthplace of that final convulsion of Europe’s long history of religious wars – the Thirty Years War, from 1618 to 1648. In the years leading up to the war, the university in Heidelberg had been a hotbed of radical ideas. And it mattered. At the time, Heidelberg University was one of Europe’s most prestigious centers of higher learning – the oldest university in Germany, established by Papal Bull in 1389. Luther and Swiss Calvinists had lectured there. The Rhenish king broke with other family members and became an early supporter of the “reformed faith.” The peoples of the valley swore their allegiance and when the Catholic armies arrived the peoples of the valley were slaughtered like nowhere else in Europe, their stories preserved in archives at the university.

But that was not the past I had journeyed with the hope of experiencing… not a closer view of Ukraine, like a war correspondent.

No.

I wanted to breath the air where the carnage came to an end.

Of course, the 1648 Peace of Westphalia did not prevent all the wars still to come, but one kind, at least. And it seemed reasonable to assume that if the idea worked then, then it might still be useful.

After getting bread and cheese and grapes at one of the many little shops in our Heidelberg neighborhood, we took off. The sun shined. It felt familiar. The air smelled like spring in Pennsylvania with just a hint of Scranton steel. The rented VW stick-shift Golf was zippy and happy to be out and about, not cramped up in the parking garage back at the airport. It decided right off that I was ok and responded. Even though I was an American, twenty years as an over-the-road trucker had taught me a thing or two and gave me international creds. Me and the little Golf got along fine, right from the start.

Unfortunately, despite all its modern quantum age German engineering, the little Golf didn’t have a real brain of its own and so it was up to our little trio of humans – my wife, Culley Jane, our oldest granddaughter, River, and me -- to navigate our way over the Rhine and across the valley from Heidelberg to Westphalia so I could experience my roots.

People in general are not usually consciously aware of the role geometry plays in the way they think. America is laid out on a pattern of straight lines intersecting at right angles; Europe is laid out on an entirely different geometry of circles and swirls. Even with the help of the navigation lady on our iPhones, we found ourselves trapped in an eddy of circles and swirls and never made it past Mannheim, on the eastern bank of the Rhine. We would think we were making progress, but then see the massive, idled, coal plant on the outskirts of the city for the third time and know we were going in circles like getting lost in a cedar swamp at night. It was starting to look like we were never going to make it to Westphalia. I think Culley Jane and River felt bad for me.

Overhead I noticed massive high voltage power lines that kept the city lit at night, now that the coal plant slept. I thought to myself: “I’ll bet those power lines are coming from France where they still have nuclear power.”

Falling through a navigational ball of rubber twine we somehow found ourselves in a small town on the outskirts of Mannheim and stopped for lunch at an Italian place with outdoor seating. The owner of the place was genuinely Italian, from just on the other side of the Alps, like between Denver and Grand Junction. He knew some English so we got to bullshitting a little. I told him I grew up in a small town where there were lots of Italians. He recognized some of the surnames. “Northern Italia,” he said with some pride.

“They were miners and brick layers and machinists,” I said.

He nodded.

We ordered our food. I got something normal. Culley Jane got something with an unpronounceable name. River got some kind of spaghetti with some kind of sea sauce on it.

One of the first things you learn about eating in restaurants in Europe is that they don’t give out doggy bags. So when we were all done River still had some spaghetti left on her plate which, normally, back in America, I’d take back home for a midnight snack. But here it was different. Who was I to say what culture was superior? I hate seeing food go to waste.

It was the worst thing I’d ever tasted in my life! It tasted like something that wasn’t dead, but should be. River laughed. “Octopus,” she said like it was nothing. “It’s good.”

In a few days we’d be in France where they eat snails.

Westphalia was still “over there.”

Lost in the Palatine. Even with the help of the navigation lady on her iPhone, Culey Jane couldn't figure out how to get us from here to there.

"Octopus," River said. "It's good."