THURSDAY'S COLUMNS

April 20, 2023

Our Story

by

Lawrence Abbe Gauthier

Ace Reporter

The Westphalia News

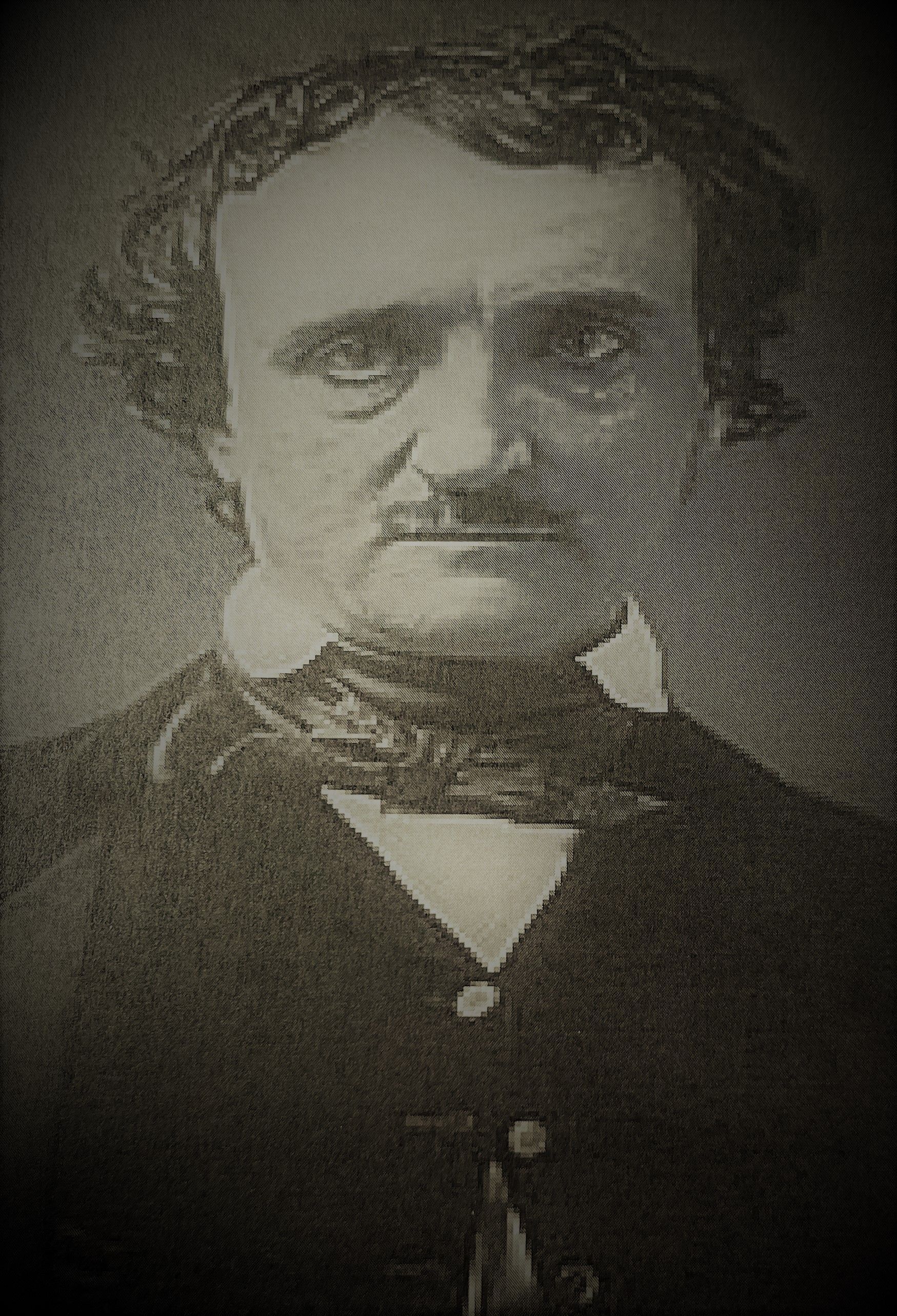

Edgar Allen Poe

Pursuing the Obvious

I'm always trying to recruit new secret agents.

When I first consciously became a secret agent back in the 70s I already was one but didn’t know it. My top boss at the time would soon be named Ronald Reagan’s choice to be his Director of the Central Intelligence Agency -- William Casey. I was his secret agent, carrying his message, but didn’t know it, or want to know it. I liked my job.

Casey had been an OSS spy during WWII. After the war, he teamed up with other OSS vets and a failed Presidential candidate – Thomas Dewey -- to create a company called Capital Cities Communications, or Cap Cities, for short. Initially, in the 50s, it bought up radio stations in state capitals along the east coast, hence the name. In the 60s it tapped into the money and influence pipeline of Resorts International, connected to Meyer Lansky’s gambling operations in Cuba. It grew. It bought up Woman’s Wear Daily and ESPN. In the 70s it started buying up major newspapers, including the Kansas City Star, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and a major Detroit metro where I was a reporter at the time. It would eventually go on to take over ABC New and Disney.

When I worked for the company starting in the mid-70s, Casey was no longer a hands-on manager of things, but he remained a large presence behind the screen. He was the company’s largest stockholder, a Wall Street lawyer and knew everybody, from Catholic archbishops to Third World dictators to members of the Board of Directors of the Bank of England. Nothing happened in the company – from the bean counters in accounting in New York to the beat reporters on the streets of America -- that was not influenced by Casey’s perspective, his view of the world, of human nature. I was one of his grunt-level secret agents but didn’t know it. I thought my ideas were my own. Like I said, I liked my job.

Then one morning in 1978, hung over at my desk in the newsroom, I got a telephone call from somebody who said his name was Pachenko. Just Pachenko. I was recruited.

It was Pachenko who told me one night drinking Stroh’s and shots of cheap whiskey that what makes a person crazy is not so much what they think as not knowing why they think the way they do.

My first assignment was to read Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, The Purloined Letter. It was a long time ago, but this is how I remember it. My wife, the professor, I’m sure, will find inaccuracies down in the weeds of the story as written by Poe, himself, in 1842, but this is how I remember it… what influenced me.

Most people don’t know that Edgar Allan Poe reportedly was a secret agent, himself, for the young American Republic and that The Purloined Letter was a manual for how to do it.

The story takes place in Paris.

It’s the early 1800s.

The main character is Dupin.

The English character, Sherlock Holmes, was modeled on Poe’s Dupin, lounging in an overstuffed chair in a darkened room; a Meerschaum pipe of opium dreams; solving riddles too complex for the untrained eye.

When the police get a case they can’t solve, they call on Dupin.

The Purloined Letter is about one such case.

The police are looking for something…. they know where it is, but they can’t find it. Or, as the likes of a Dupin would realize right off the bat, they knew where to look, but couldn’t see it.

The police were looking for a letter, a stolen (purloined) letter that, if made public, would greatly embarrass certain influential public officials.

They knew the identity of the thief. And they knew that the letter was still hidden inside the thief’s apartment. But when they entered the apartment one night while the thief was away, they couldn’t find the letter… anywhere.

Somebody said: “This is a case for Dupin!”

Dupin nodded to them when they entered his darkened room. They nodded back. They all knew one another.

They filled Dupin in on the details of the case and how they’d probed the apartment’s every crevice and nook with needles and scopes and with the most thorough and modern techniques of discovery. They were beside themselves with bewilderment and frustration and under intense political pressure to achieve results.

Dupin listened to their story, thought about it, then took off through the darkened streets of Paris to the apartment and came back with the letter in hand.

Once again, the police were astounded by Dupin’s skill!

As Sherlock Holmes would have put it years later, Dupin replied: “Elementary, my dear Watson.”

Here the details are fogged in my aging brain, but the way I remember it the letter had been attached to the end of a string dangling from the mantelpiece of the fireplace in the main room in plain sight.

“Of course,” the police murmured amongst themselves. “It was so… so obvious! Why hadn’t we seen it?”