Thursday's Columns

July 13, 2023

Culley Jane and River, creating memories out of First Impressions

Our Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

Descending into the Past

Americans in Europe

(Part 5)

We’ve been back for a month now, so I’m writing from memory aided by Wikipedia, not first impressions.

Tracing the bewildering historical lines of succession of Europe’s inbred royal families is not what I was born to spend a lot of time on. But since we spent the better part of our second day in Europe exploring Heidelberg Castle, it seems appropriate.

Starting in England…

The Tudor family ruled England from1485 to 1603.

The Stuart clan from up north in Scotland took over in 1603 and ruled England until 1714.

Most people don’t know (I didn’t until recent years) that in 1714 the English crown went to a German and that his ancestors have been England's kings and queens ever since. What could be more ethnically English than its Royalty? But it’s true.

The first German King of England was George I. As I sit here at my computer back in America writing, it’s July 2, two days before the Fourth of July, our Independence Day, the day we withdrew our allegiance to George I’s grandson, George III. The Georges I, II and III had lots of children in the 18th century – George II, alone, had 13. I imagine that to this day the offspring of their offspring still inhabit a good chunk of the upper crust of English society, probably in publishing and finance and politics.

How Germans became English kings was the story I wanted to tell, not so much for historical reasons, but philosophical.

The story begins at Heidelberg Castle when a 16-year-old Scottish girl first arrives. It’s 1613. Her name is Elizabeth. She’s a member of Scotland’s famous Stuart clan, which had ruled that country since the 14th century.

Elizabeth’s father was the King of Scotland when she was born in 1596. Following the “Union of the Crowns” in 1603, he was also made King of England and Ireland, as well.

Elizabeth grew up in typically royal fashion and when she was married on Valentine’s Day in 1613, royalty from all over came to England for the event. Had it happened four centuries later it might have gotten a spot on CNN.

Her husband had been chosen carefully, picked above dozens of other high-profile suitors from all over Europe, including the King of Sweden. Elizabeth first saw her selected spouse when he arrived in England for the wedding. His name was Frederick. They were the same age, which seldom counted for much when dynastic unions were being arranged. Many of the king’s advisors urged him to choose the much older Swedish suiter. With a family claimant to Sweden’s vast areas of taxable land, resources and labor to loot, advisors recognized the realistic potential for rich rewards.

But the girl’s father, the King, got to give the final word, and he chose Frederick. Not that Frederick was a nobody. Though just 16, himself, he ruled over the Rhenish Palatinate in Germany as Frederick V. His family, the Wittelsbachs, had ruled over that area of the Rhine Valley for centuries. They had the power to construct tolling gates along the river and the means of enforcement. The soil was black and well-watered. But the Rhenish Palatinate was no Sweden. Its greatest value, in the King’s eyes, was its religion, shared by its ruler. The young Frederick was a Protestant, but not just any kind of Protestant. He’d been raised in the strict Calvinism that had come down the Rhine from Switzerland during the previous century, pollinating the Palatinate with the “reformed faith.”

Back then, Catholics and Calvinists mixed like oil and water, not good in a marriage. But Elizabeth had been raised to be flexible. The Stuart family, like all of Scotland, had been staunchly Catholic for centuries. But things had changed. During the previous century, the Scottish people began flocking to the new ideas of the reformed faith. In 1560, the Scottish Parliament made it official, passing a law making the new ideas the law of the land. So Elizabeth’s genealogically Catholic father had to do a tip-toe dance down a treacherous path. To do anything pleasing to Rome got the Protestants in an uproar, and visa versa. He hoped that by marrying his daughter off to a Protestant leader in Europe that it would help to smooth some feathers back home. It didn’t, of course. It was against the Catholic Stuart kings of the 17th century that England’s “Glorious Revolution” was waged. One of them, Elizabeth’s younger brother, was beheaded.

By all accounts, Elizabeth and Frederick had a faithful and loving marriage. She became a Protestant, and the children were raised that way. But it wasn’t like the handsome prince bringing Cinderella home to his castle where they lived happily ever after. Certainly, it was productive. Although Frederick was often away raising and leading armies during the 30 Years War, they had 13 children, which is amazing when you stop to pencil it out. Frederick was just 36 years old when he died from an infection while off on another mission during the religious warfare that was reducing Europe’s population in some places by up to 50 percent. So, they were only married for 19 years. and they had 13 children. Yes, it was certainly productive, especially considering that for most of it they lived as exiles on the run in a world in flames over a clash of ideas.

The young couple first arrived at Heidelberg Castle in 1613. Their journey to Heidelberg from London, where they were married, had taken all of two months… a royal caravan of hundreds of wagons and carriages, horses, servants, retainers, medieval knights hoisting banners at the tips of long, polished silver spears. Passing through towns and villages on their journey up the Rhine Valley, children, housewives and thrashers of grain were struck with awe.

What, I wonder, sitting here writing about it at my computer four centuries later, were the teenage bride's first impressions of Heidelberg Castle at the end of such a journey. Of course, I could never know that. Even Elizabeth only knew it in the instant and then it became her memory and then the abstract research of archeologists and historians.

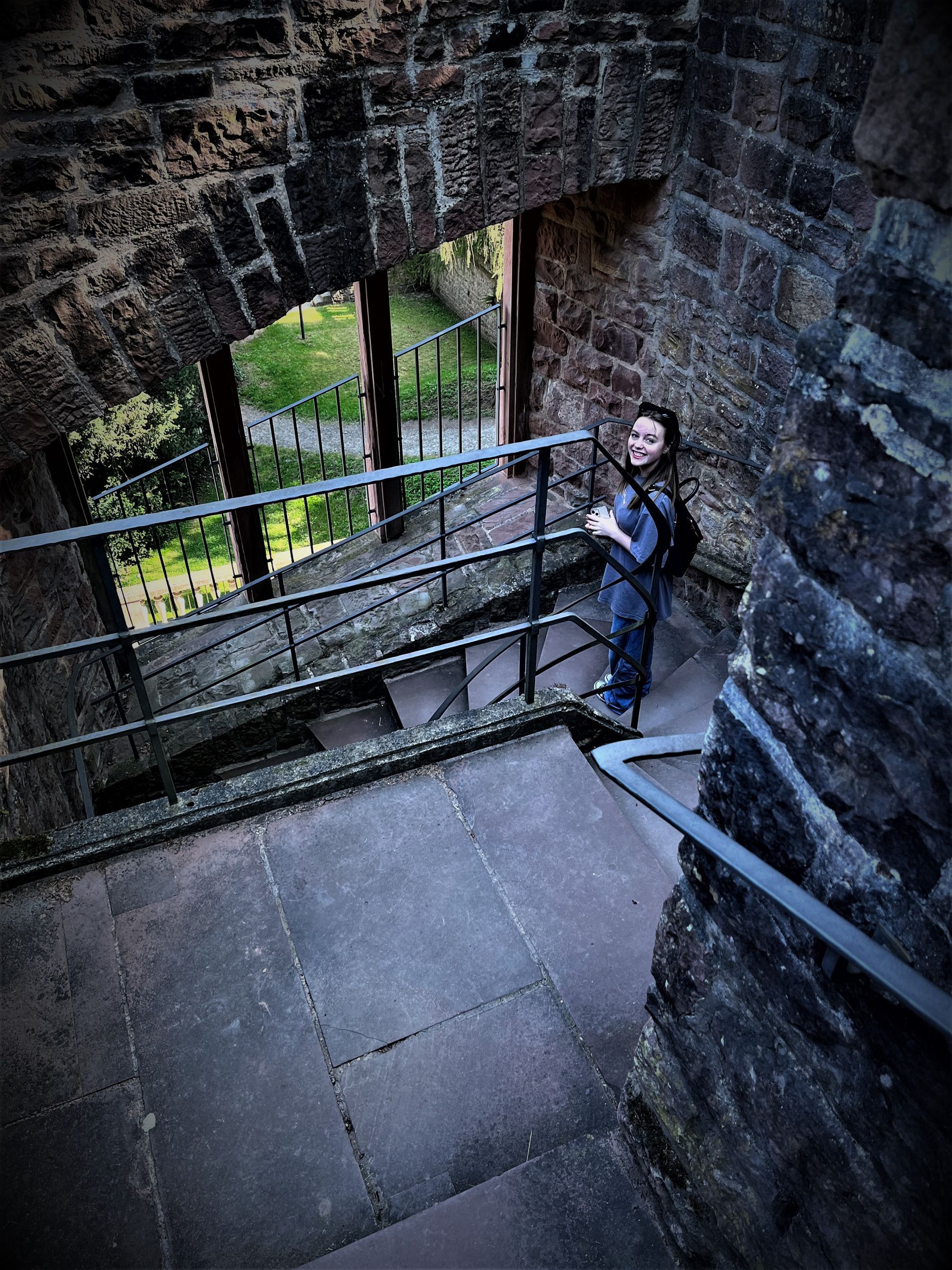

Our 16-year-old granddaughter, River, only truly knew her first impressions the moment she entered the historical site through the gate in a massive stone wall. And then, just as quickly, they became memories. But I’ll bet she’ll never forget the wooden wine barrel, as big as a house – biggest in the world. I saw her eyes widen, like Dorothy of Oz, catching a glimpse of another world behind the forbidden curtain. Maybe it was not a big deal to Elizabeth, who grew up in royal palaces, but River had grown up regularly -- starting with apartments, then a condo and now a house at the eastern edge of the Denver metropolitan area with a view of the endless high plains to the east. She’d always eaten her meals at a table in a kitchen with a refrigerator and dishwasher. At first, we think that everybody lives like we do; that the sun goes around us. Then a curtain is parted.

The castle’s great dining hall was as big as a hockey rink. The biggest wine barrel in the world said it all. I thought to myself: “If only the wine barrel were alive to tell the stories of what it was really like, back then, when Elizabeth and Frederick were newlyweds and in love.” Maybe River was thinking the same thing. Maybe the Cinderella story was real, after all.

But Elizabeth and Frederick only lived in the castle for six years. In 1619, Protestant princes in Bohemia deposed their Catholic king and asked Frederick to be their new king. So the young family (they already had three children) moved from Heidelberg Castle to a castle in Bohemia, to the west of the Rhine Valley across a mountainous sloping shoulder of the Alps.

Elizabeth was seven months pregnant with their fourth child when, on November 8, 1620, the Catholic army arrived to restore Catholic rule in Bohemia and serve as an example to restless Protestants in other areas of the Holy Roman Empire. The Catholic army with 23,000 well trained and supplied soldiers easily routed the more ragtag outfit of 20,000 Protestants. Elizabeth could hear the distant sound of cannon. Historians call it the Battle of White Mountain and generally agree that it was beginning of the Thirty Years War.

The Catholic powers stripped Frederick of all his ancestral rights and titles. The young family was homeless, exiled, on the run.

Fortunately, Elizabeth had relatives in the Protestant Netherlands. It wouldn’t be like everybody cramped into an apartment. Her relatives were of royal lines.

When the 30 Years War was finally ended in1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, title to the Rhenish Palatinate and the castle was returned to Elizabeth. She was 52 years old. Frederick had been gone for 16 years. It was all just a memory. She couldn’t go back... not really.

The Stories it Could Tell