Thursday's Columns

August 10, 2023

Our Story

by

Lawrence Abby Gauthier

ace reporter

The Westphalia Periodic News

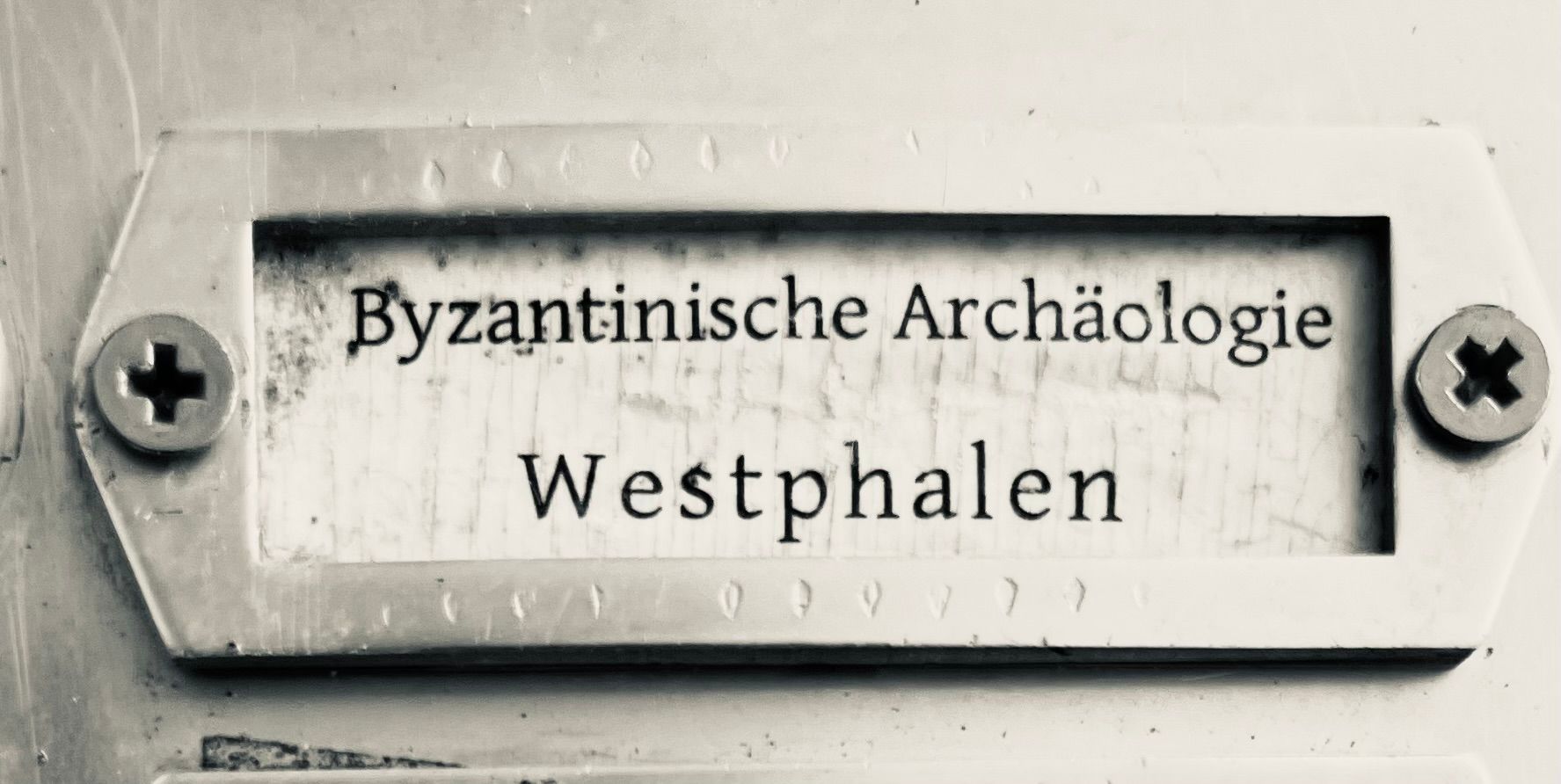

River hamming it up.

Americans in Europe

(Part 9)

I’d seen enough of Heidelberg and was getting antsy to get back on the road and on to France.

In just the two days we’d spent in the old capital of the Rhenish Palatinate, I’d gathered up enough investigative leads to follow to last me for the rest of my life. The whole story of the rise and fall of the British Empire and the lingering shadow of its money could be traced back to this small German city. I was sure of it. But documenting the connections would require a lot of research and I was getting anxious to get to France. My French-speaking great-grandfather Thibault told us kids stories about France. He’d first heard the stories from his father. I wanted to see for myself if it was like what he said.

On our third and final day in Heidelberg I got up on the wrong side of the bed. I was going to use the trip to Europe as a springboard to finally quit smoking. Culley Jane, my wife, was a little pissed about it -- not that I was trying to quit smoking, but that I hadn’t told her about it so she didn’t know why I was being the way I was.

It was a Sunday.

My feet were sore.

All the little local stores where they sold bread and grapes and cheese were closed because it was Sunday. Our fifteen-year-old granddaughter, River, had never known a Sunday when all the stores were closed just because it was Sunday. I hadn’t, either, at least not since I was a kid. I think it started to change in the 60s, but apparently not so much in Europe.

We had decided to spend our final day in Heidelberg visiting the historic Heidelberg University.

It was a six or seven-block walk from our lodging to the Necker River, which flows through the town before it dumps into the Rhine up around Frankfort. Then we would follow a tourist walkway another five or six blocks along the river to the main campus on its original site.

I’d read in tourist brochures and on the internet that remnants of the university’s medieval structures could still be seen and that it was the oldest university in Germany, established in 1388 at the direction of a pope.

I learned that Heidelberg University had been a hotbed of religious heterodoxy for a hundred years before the philosophical tensions erupted into fire, engulfing Europe in the Thirty Years War. By the time the killing stopped, half the people of the Rhenish Palatinate had perished. A lucky few made it to America.

The war ended in 1648 when everybody agreed to the terms of the “Peace of Westphalia."

When you stopped to think about it, it was an amazing thing. With the stroke of a pen, religious wars that had been going on for what seemed like forever finally ended, like getting to the last page of a long book; close the cover and put it away on a shelf. From then on, other excuses would have to be found to go to war, but no more strictly religious wars would be fought in Europe. England’s “Glorious Revolution” was sold to the public as a political issue – a squabble between Parliament and the King over the meaning of words like “rights” and “authority.” By the 20th century the excuses became racial, cultural, economic. Communists, my Dominican teachers said, were “godless,” but that wasn’t the main reason to be afraid of them. They were “communists.” That was enough.

After taking showers and getting stuff from the vending machines in the basement of our lodging, we took off walking in the direction of Heidelberg University. Miraculously, just as the town’s Sunday church bells began to echo back and forth across the valley, we passed by a little pharmacy that was open and I got a pack of nicotine gum.

Walking along the river, I noticed boats filled with tourists sitting on deck chairs looking up at the castle. Hillsides lush with grapes. The asparagus raised by local farmers grew to the size of big carrots. I was starting to feel better.

“The trip’s been great so far,” I told my two travel companions. “I just wish we’d of made it to Westphalia so I could of taken a picture there.”

I didn’t expect anybody to really understand why taking a picture in Westphalia was so important to me. I wasn’t sure myself. You can get any kind of picture you want on the internet, but a newspaper reporter is expected to be on the scene. Any kind of picture would do -- of a café or a sign along the highway. Anything as long as the word “Westphalia” was in it. Like the signs in America when you cross into a new state, the perfect one would say:

WELCOME TO WESTPHALIA

Birthplace of the Peace

But as I explained in an earlier column, we never made it to the Westphalia region of western Germany, near its borders with the Netherlands. We tried to drive there in our rented VW Golf, but got disoriented and lost in a tangle of roadways first laid out during Roman times and we had to retreat back to Heidelberg, feeling a little defeated. But then we visited the castle and I started getting into the story of Elizabeth Stuart and her daughter, Sophia. I had a hunch it was at the heart of a bigger story, maybe the biggest. When I was a young reporter they used to say I had a “nose for news,” an instinct. I hoped to pick up a few more clues at the university.

The university’s main campus was ringed by streets lined with small shops on the ground floor of old buildings with fresh paint. The streets were for people – students, faculty, tourists… walking around, at tables, talking, reading, watching, romancing. Most of the stores were closed, but not all of them. I bought a Heidelberg University t-shirt. River got ice cream at a sidewalk café. Culley Jane translated. It seemed like everybody was smoking a cigarette. The streets were littered with butts.

We left the hectic street scene to wander around in the old campus. It was Sunday. It was quiet. We found ourselves pretty much alone in something like a central courtyard. A pigeon landed, just like in a movie.

The courtyard was surrounded by buildings built out of stone a long time ago but built to outlast generations. I imagined it took a lot of maintenance to get, and then to keep them up to code, but it was still a place where many of the world’s great minds would go to work come Monday morning. A free brochure I’d picked up listed dozens of current and former faculty members who had won the nation’s most prestigious award for academic research -- the Leibniz Prize.

I sat down on a stone bench in the center of the courtyard. While Culley Jane and River wandered off towards the buildings, I just sat there, alone, with my thoughts. The castle in the distance.

Pretty soon Culley Jane and River came back. They said they had something to show me.

Next to one of the buildings’ entranceways was a directory of the various departments located there.

One of them jumped out at me.

River hammed it up.

I took a picture.